El proyecto de Marcelo Brodsky ofrece una narrativa subjetiva en la que la fotografía actúa como memoria.Comprometido con la lucha por defender causas sociales estrictamente relacionadas con los derechos de la humanidad, su trabajo se relaciona en gran parte con situaciones inherentes a la violencia en los tiempos de dictadura militar en la Argentina (1976-1983), la persecución y desaparición de ciudadanos, haciendo eco en el panorama internacional, representando a las voces de los pueblos que denuncian el terrorismo de Estado organizado en cualquier territorio.

La fotografía en su obra es un testigo, una suerte de “servicio documental” al ser trabajadas combinando material de archivo y documentación que el artista inscribe sobre las imágenes condensando experiencias traumáticas, vestigios de vivencias ligadas al horror y el exilio. Marcas, notas, colores, el tono lacónico, archivístico, de la información alude al discurso impersonal de la historia; la caligrafía, desprolija y urgida, invaden las fotografías señalando, destacando, acentuando las faltas, los vacios provocados por aquellos que ya no están, o los reclamos de una sociedad. Su trabajo construye memoria en el tiempo, un puente invisible el cual con sus grafismos, conecta décadas y desafía al olvido revelando la presencia de los cuerpos silenciosos que hablan desde un pasado no muy lejano. Al trasponer materiales vernáculos familiares y el testimonio personal en la esfera pública, el artista otorga una oportunidad para que otros puedan identificarse y conmoverse, permitiendo la comprensión de sucesos lejanos. Al regresar de su exilio en España, Brodsky utilizó fotografías familiares como punto de partida para un cuerpo de obras que tratan de comunicar el trauma de la experiencia vivida. El artista se posiciona desde una experiencia personal para invitar al espectador a conmoverse, identificarse, generar empatía con el otro y crear un espacio común de reflexión donde las memorias individuales puedan convertirse en colectivas. Su obra se despliega en múltiples soportes dentro de las artes visuales y las publicaciones editoriales donde la imagen se activa como documento haciendo difusos los límites entre lo artístico, el trabajo de archivo, los videos, las instalaciones, entre otros. Brodsky explora la capacidad de la fotografía para proporcionar un espacio de meditación entre la memoria privada y las historias colectivas. Es gracias a su absoluto conocimiento del uso del poder de las imágenes, y de la palabra, que Marcelo Brodsky logra a través de sus obras transmitir un mensaje que nos compromete como individuos políticos.

Marcelo Brodsky’s project offers a subjective narrative in which photography acts as memory. Committed with the fight to defend social causes strictly related to the human rights, his work is largely related to situations inherent in violence in the times of military dictatorship in Argentina (1976-1983), the persecution and disappearance of citizens, echoing on the international scene, representing the voices of the peoples who denounce organized State terrorism in any territory.

The photography in his work is a witness, a kind of “documentary service” when they combine archive material and documentation that the artist inscribes on the images, condensing traumatic experiences, vestiges of situations linked to horror and exile. Marks, notes, colors, the laconic, archival tone of the information alludes to the impersonal discourse of history; calligraphy, untidy and urgent, invade the photographs pointing out, highlighting, accentuating the faults, the gaps caused by those who are no longer there, or the demands of a society. His work creates memory in time, an invisible bridge which, with its graphics, connects decades and defies oblivion, revealing the presence of silent bodies that speak from a not too distant past. By transposing familiar vernacular materials and personal testimony in the public sphere, the artist provides an opportunity for others to identify and be moved, allowing understanding of distant events. Upon returning from his exile in Spain, Brodsky used family photographs as a starting point for works that try to communicate the trauma of the lived experience. The artist positions himself from a personal point of view to invite the spectator to be moved, identify, generate empathy with the other and create a common space for reflection where individual memories can become collective. His work is displayed in multiple supports within the visual arts and editorial publications where the image is activated as a document blurring the limits between the artistic, the archive work, the videos, the installations, among others. Brodsky explores the ability of photography to provide a space for meditation between private memory and collective stories. It is thanks to his absolute knowledge of the use of the power of images and of the word that Marcelo Brodsky manages to transmit through his works a message that commits us as political individuals.

Marcelo Brodsky (Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1954) es un comprometido artista visual y activista de derechos humanos.

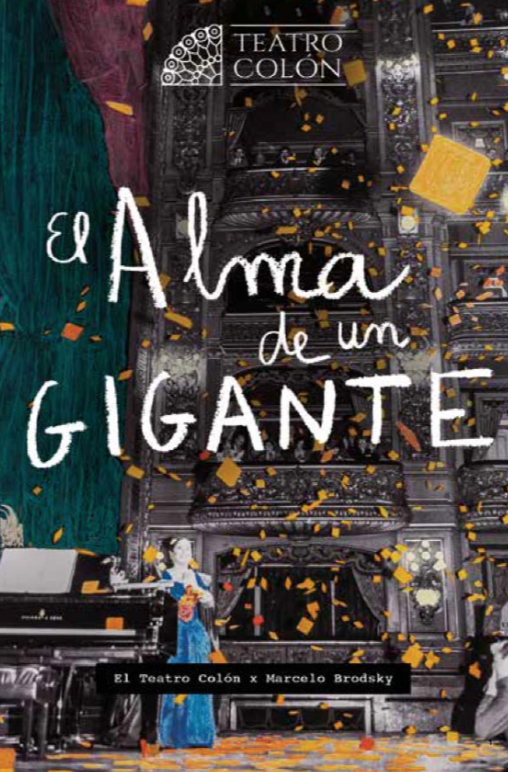

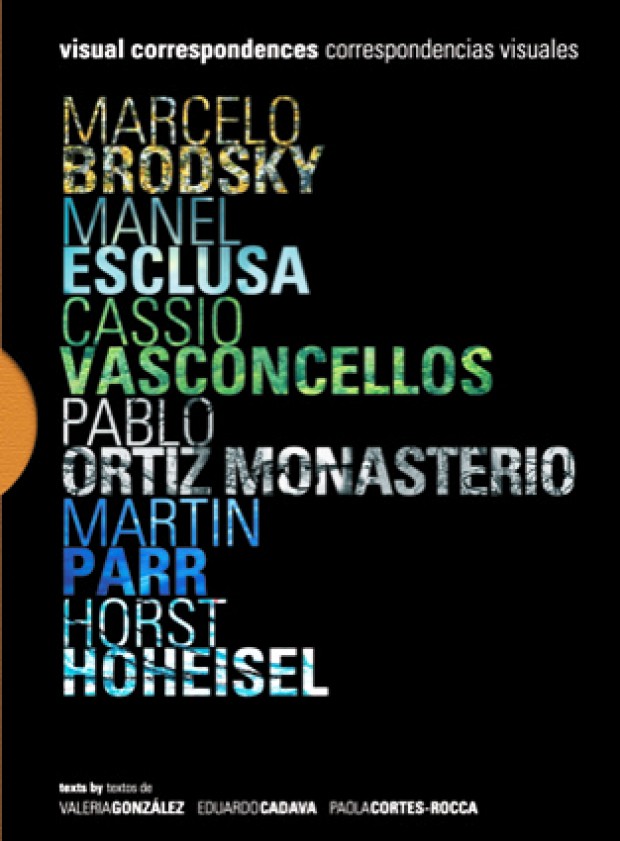

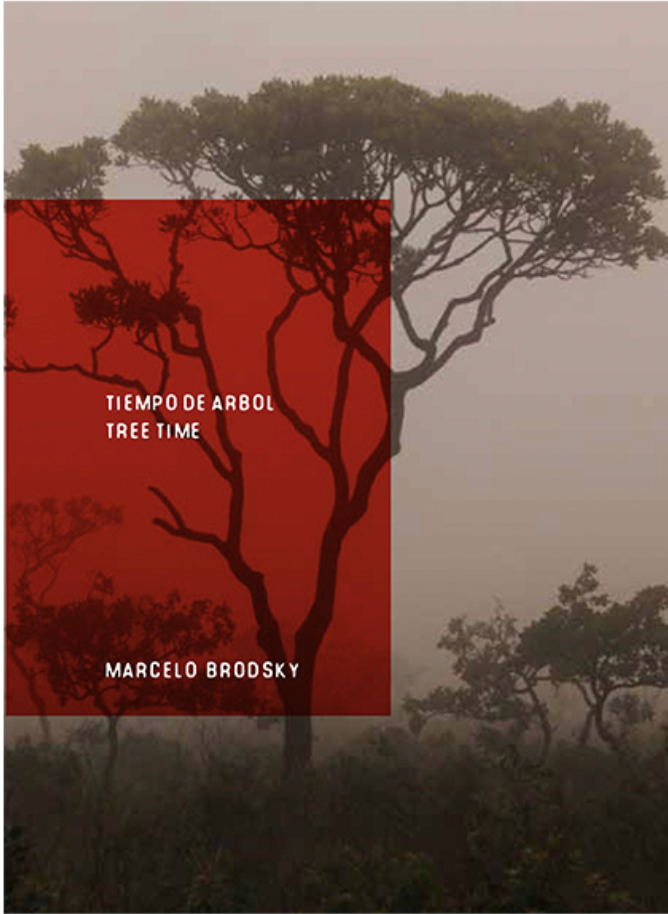

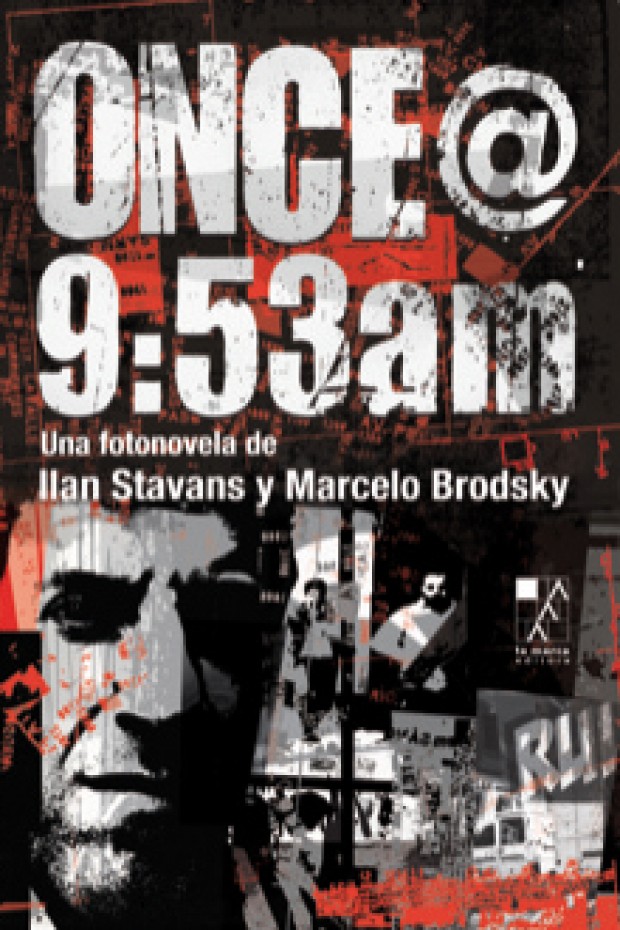

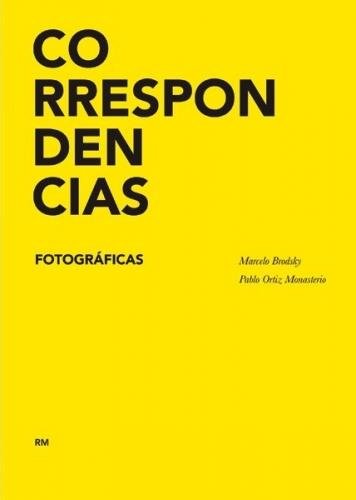

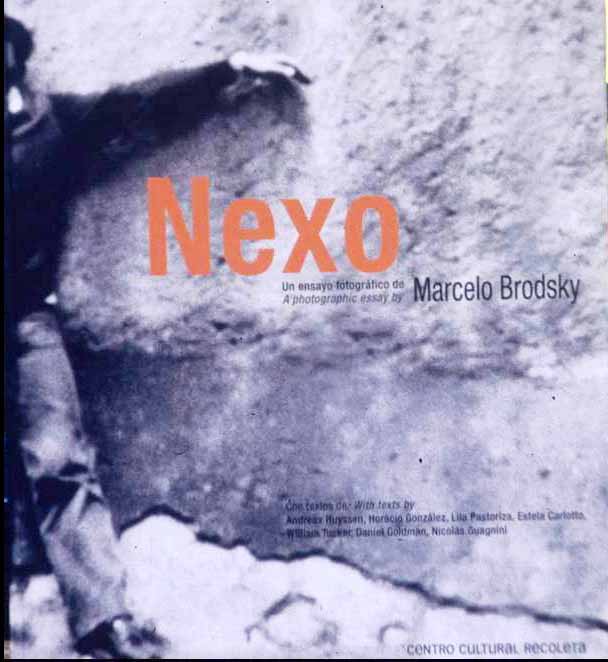

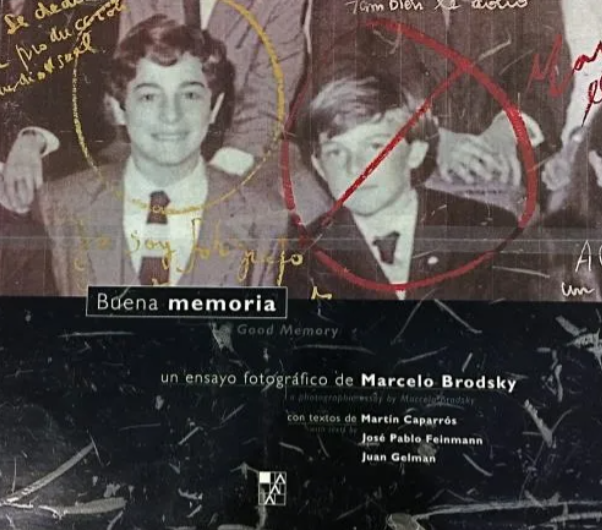

Ha representado a la Argentina en diversas bienales internacionales incluyendo Bienal de Lyon (2017/18) Photoespaña y el Festival de Arles (2018) Dakar (2018), San Pablo (2010), Valencia (2007), Rotterdam (2000), entre otras. Ha sido galardonado con numerosos premios y reconocimientos, tales como el Jean Mayer Award de Ciudadania Global por la Universidad de Tufts, Boston (2015), el Premio Derechos Humanos, otorgado por la Organización Bnai Brith (2003), entre otros. Ha publicado numerosos libros tales como “1968 el Fuego de las Ideas” ( 2018), Poeticas de la Resistencia (2019), Tiempo del Árbol (2013), Correspondencias visuales (2009), Correspondencias Pablo Ortiz Monasterio – Marcelo Brodsky (2008), Correspondencias Martin Parr – Marcelo Brodsky (2008), El alma de los edificios con Horst Hoheisel, Andreas Knitz y Fulvia Molina (2004), La memoria trabaja (2003), Nexo (2001), Buena Memoria (2000), Parábola (1982), entre otros. Su obra ha sido catalogada en importantes publicaciones líderes tanto nacionales e internacionales. Ha realizado numerosas exposiciones individuales y grupales en países tales como Argentina, Brasil, Chile, Uruguay, Perú, España, Francia, Alemania, Suiza, Italia, República Checa, Reino Unido, Israel, y Estados Unidos, entre otros. Hoy en día, su obra integra colecciones nacionales e internacionales tanto públicas como privadas como el Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes – MNBA (Buenos Aires, Argentina); Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires – MAMBA (Buenos Aires, Argentina); Banco de la República de Bogota (Colombia); Pinacoteca del Estado de San Pablo (Brasil); Bibliothèque Nationale (Paris, France); Museo de Fine Arts Houston (MFAH), Princeton Art Museum, The Centre for Creative Photography, University of Arizona Foundation (Arizona, Estados Unidos); Sprengel Museum Hannover (Hannover, Alemania); Colección de arte contemporáneo de la Universidad de Salamanca (Salamanca, España); University of Essex Collection of Latin American Art (Colchester, Reino Unido); TATE Collection (Londres, Reino Unido); MET The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Nueva York, Estados Unidos); Jewish Museum (Nueva York, Estados Unidos) entre otras. Vive y trabaja en Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Marcelo Brodsky (Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1954) is a committed artist and human right activist.

Brodsky has represented Argentina in several international biennials such as Lyon Biennale (2017/18), Photoespaña and Les Rencontres d’Arles (2018), Dakar (2018), San Pablo (2010), Valencia (2007), Rotterdam (2000), among others. He has been awarded with distinctions and received many accolades, such as the Jean Mayer Award of Global Citizenship at Tufts University, Boston (2015), The Human Rights Award by Bnai Brith Organization (2003), among others. He has published numerous books such as “1968: The fire of ideas” (2018), Poetics of Resistance (2019), Tree Time (2013); Visual Correspondences (2009); Correspondences Pablo Ortiz Monasterio – Marcelo Brodsky (2008); Correspondences Martin Parr – Marcelo Brodsky (2008); Vislumbres (2005); The soul of the Buildings with Horst Hoheisel, Andreas Knitz and Fulvia Molina (2004); Memory Works (2003); Nexo (2001); Buena Memoria (2000); Parábola (1982), among others. He has been featured in important leading national and international publications. His work has been shown in numerous solo and group exhibitions in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Uruguay, Peru, Spain, France, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Czech Republic, United Kingdom, Israel and USA, among others. Nowadays, his work is part of important national and international collections such as National MNBA – Museum of Fine Arts (Buenos Aires, Argentina); MAMBA – Modern Art Museum of Buenos Aires (Buenos Aires, Argentina); Banco de la República de Bogotá (Colombia); Pinacoteca from São Paulo State (Brazil); Bibliothèque Nationale (Paris, France); Museum of Fine Arts Houston – MFAH (USA); Princeton Art Museum (USA); The Centre for Creative Photography, University of Arizona, Foundation and ASU Art Museum (Arizona, United States); Sprengel Museum Hannover (Hannover, Germany); Contemporary art collection from Salamanca’s University (Spain); University of Essex Collection of Latin American Art (Colchester, United Kingdom); TATE Collection (London, United Kingdom); MET The Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, United States); Jewish Museum (New York, United States), among others. He lives and works in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

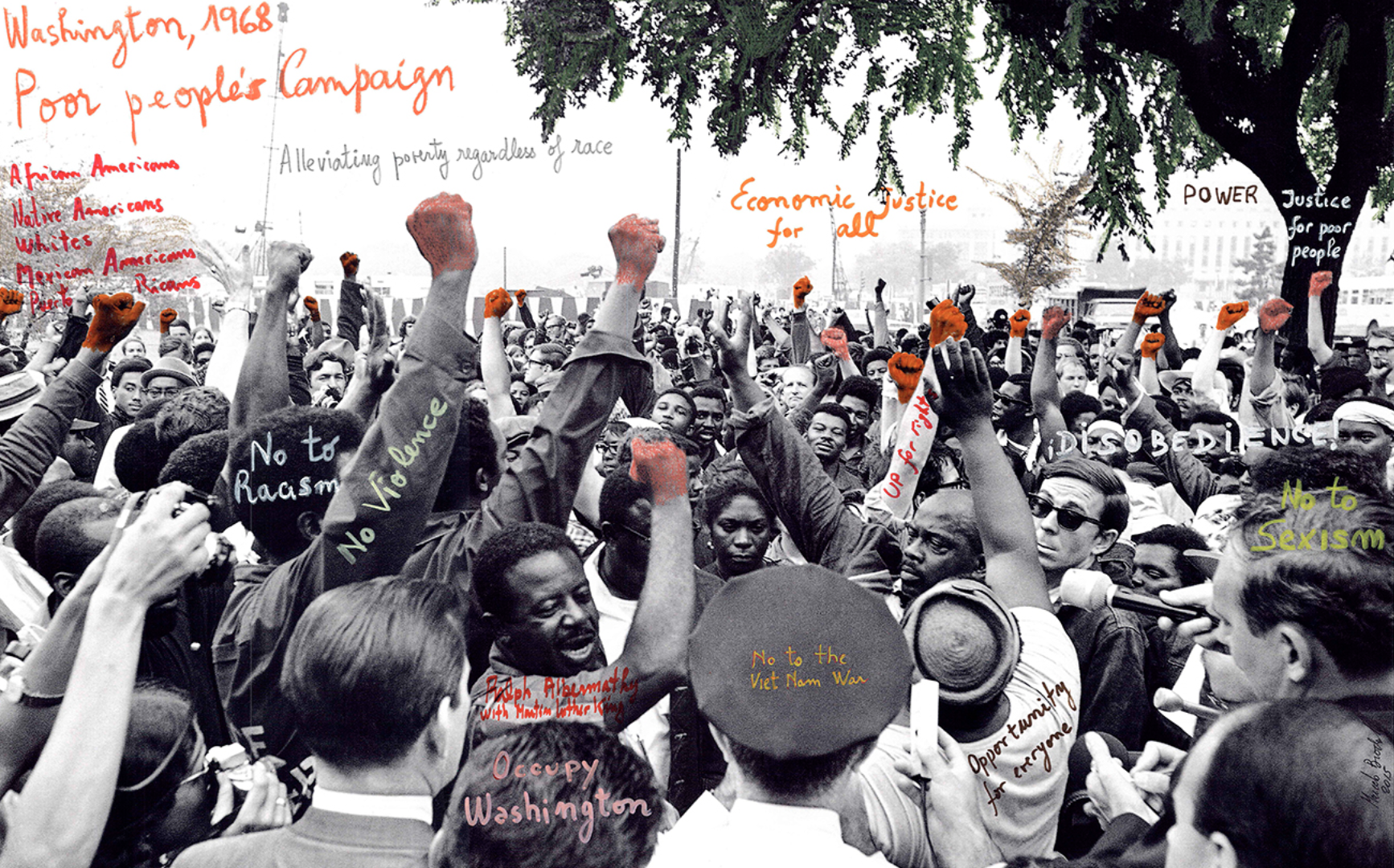

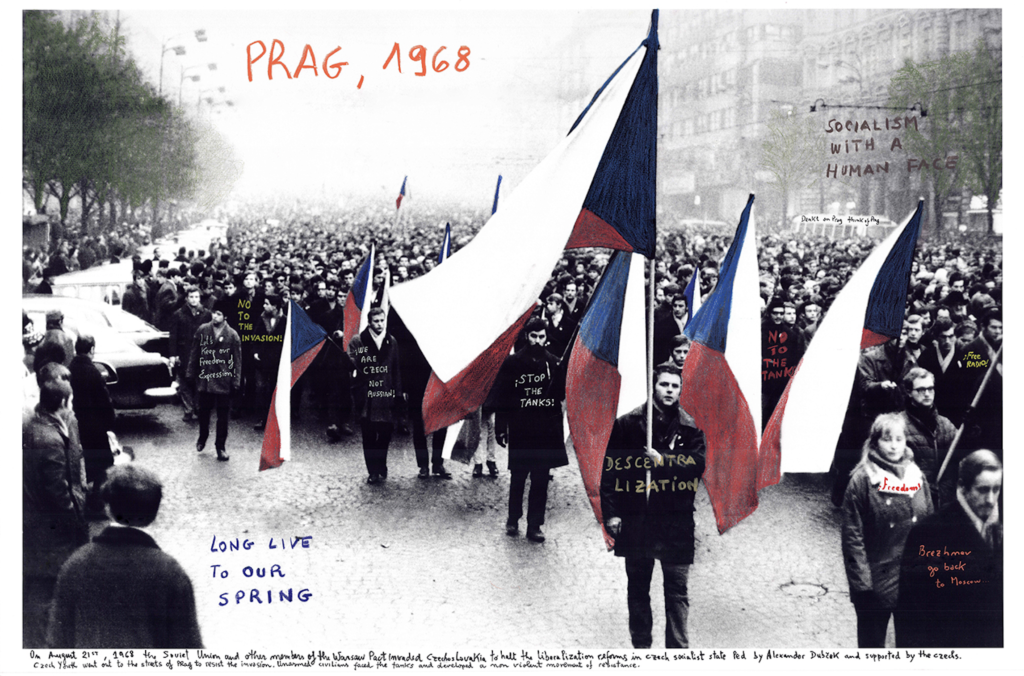

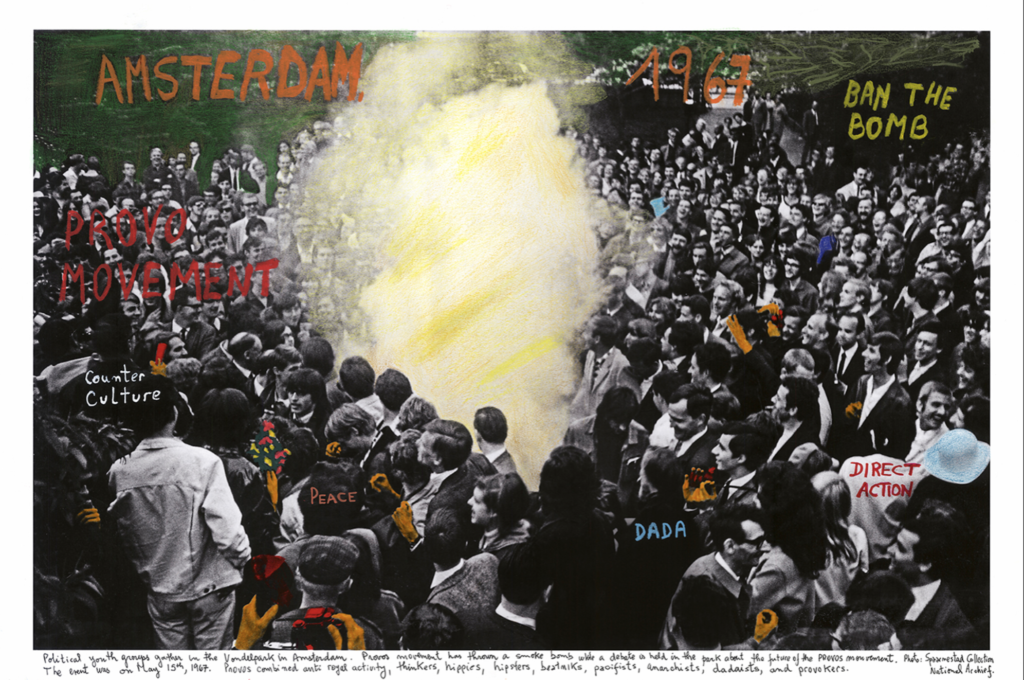

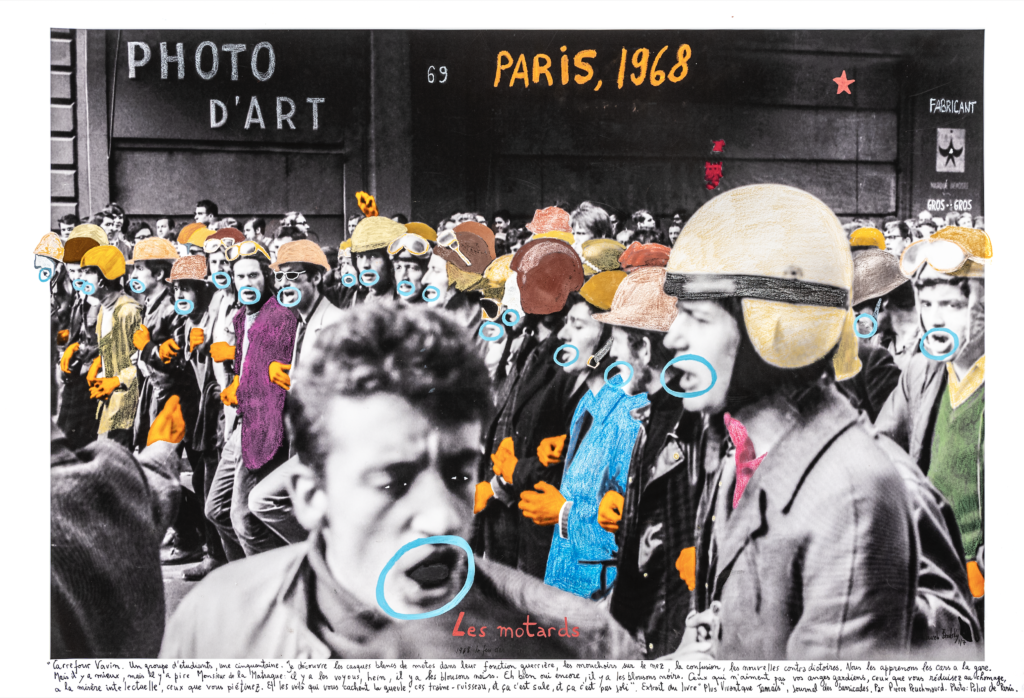

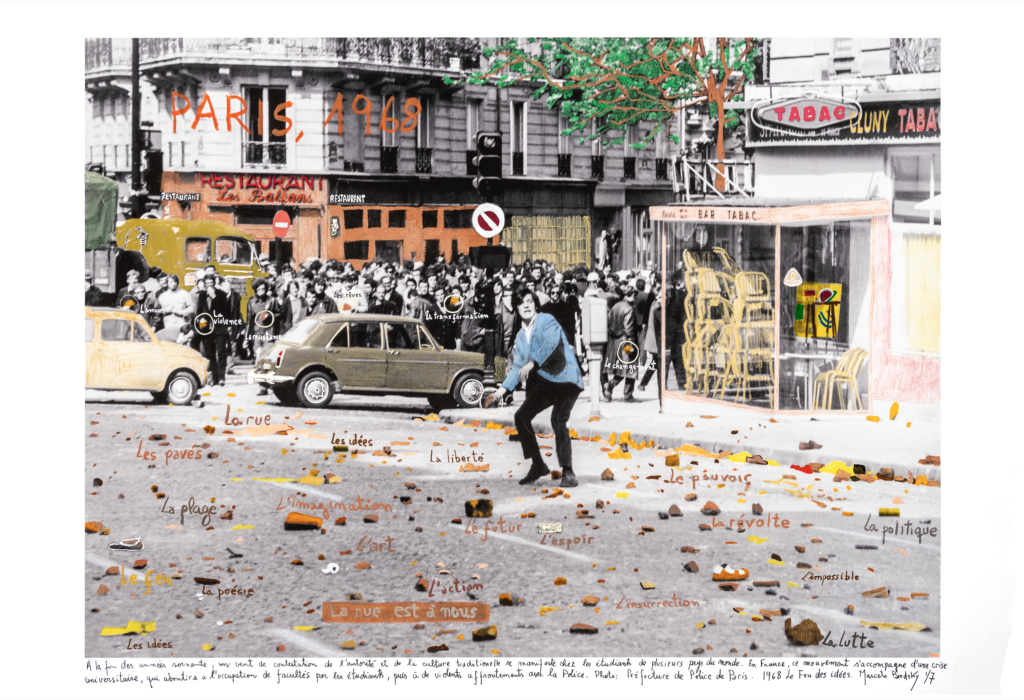

En “1968: El fuego de las ideas” Brodsky presenta movilizaciones estudiantiles y relaciona eventos sucedidos en Argentina con la turbulencia social en todo el mundo a finales de los años sesenta. Los manifestantes estadounidenses que participaron de la Marcha de los Pobres en Washington liderada por Martin Luther King unos meses antes de su asesinato; los manifestantes en Londres en contra de la Guerra de Vietnam; en Bogotá, México, Córdoba, Río de Janeiro y San Pablo, trabajadores y estudiantes haciendo campaña juntos, en contra de los regímenes militares y otros tipos de estructuras de gobierno. Se los muestra con brazos estrechados, con banderas ondulantes y pancartas, ejerciendo una acción urbana masiva para reclamar por sus demandas. Las obras también incluyen extractos de discursos de Martin Luther King, el Che Guevara, Daniel Cohn Bendit, Herbert Marcuse y Agustín Tosco, cuyas ideas y acciones nutrieron a muchos de los manifestantes.

En una pancarta de la manifestación del Mayo Francés de 1968 se muestra, el grito de “L’imagination au pouvoir” (la imaginación al poder). Más que un llamado a “decir la verdad al poder” que sonaba en otras manifestaciones de la época, los parisinos pedían por el fin de todos los límites, incluso en la imaginación.

Brodsky es pragmático y directo. No pretende liberar la imaginación de toda restricción, sino potenciar su uso contra el poder corrupto y brutal. Tanto si nos invita a aprender, y a no olvidar jamás las atrocidades del pasado, nos insta a honrar a los líderes justos y a mantener la presión sobre las autoridades hasta resolver y enjuiciar a los responsables de los más recientes asesinatos en masa, aún impunes.

Fotografía de archivo blanco y negro © Associated Press, 1968, intervenida con textos a mano por Marcelo Brodsky, 2015

Impresión con tintas de pigmentos duros sobre papel Hahnemülhe

60 x 90 cm.

Edición 7 + A/P

Black and white archival photograph © Associated Press, 1968, intervened with handwritten texts by Marcelo Brodsky, 2015

Print with hard pigment inks on Hahnemühle paper

23,6 x 35,4 in.

Edition 7 + A/P

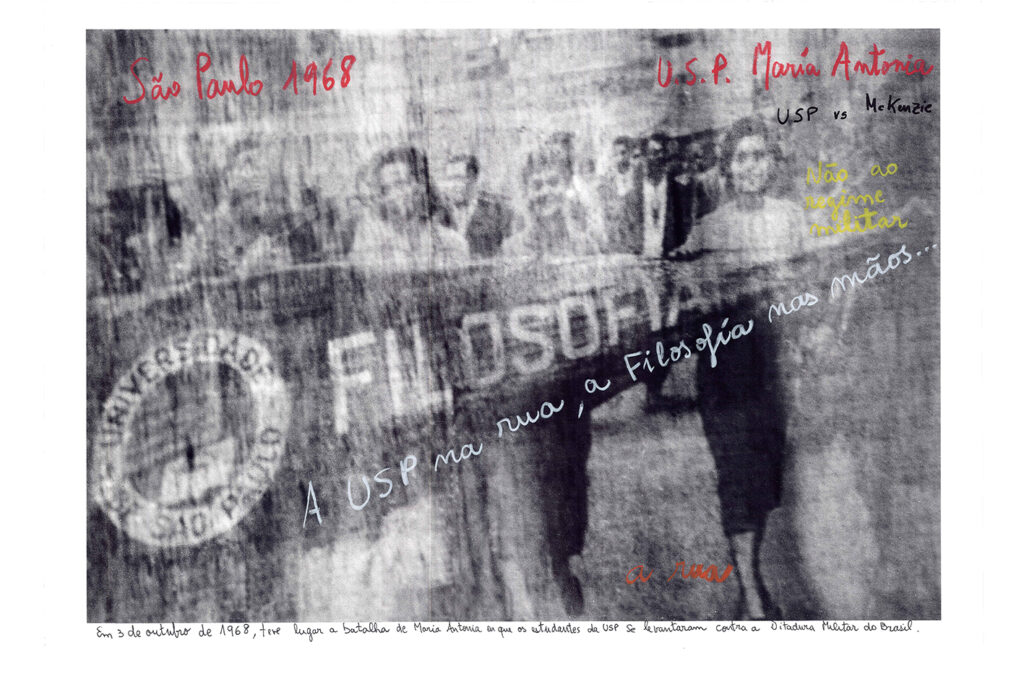

Fotografía de archivo blanco y negro © Eduardo Martinelli, 1969, intervenida con textos a mano por Marcelo Brodsky, 2014

Impresión con tintas de pigmentos duros sobre papel Hahnemülhe

60 x 90 cm.

Edición 7 + A/P

Black and white archival photograph © Eduardo Martinelli, 1969, intervened with handwritten texts by Marcelo Brodsky, 2014

Print with hard pigment inks on Hahnemühle paper

23,6 x 35,4 in.

Edition 7 + A/P

Fotografía de archivo blanco y negro © Manuel Bidermanas,1968, intervenida con textos a mano por Marcelo Brodsky, 2014

Impresión con tintas de pigmentos duros sobre papel Hahnemülhe

60 x 90 cm.

Edición 7 + A/P

Black and white archival photograph © Manuel Bidermanas,1968, intervened with handwritten texts by Marcelo Brodsky, 2014

Print with hard pigment inks on Hahnemühle paper

23,6 x 35,4 in.

Edition 7 + A/P

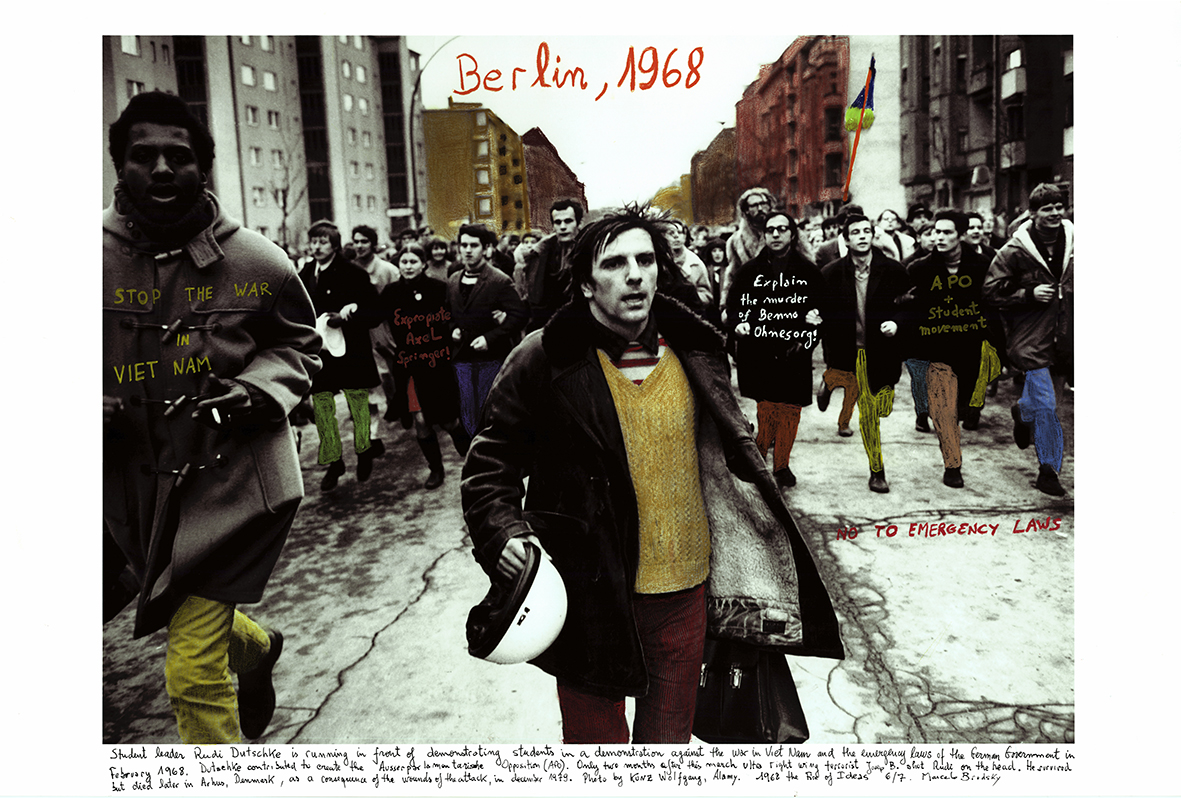

Fotografía de archivo blanco y negro © Wolfgang Kunz, 1968, intervenida con textos a mano por Marcelo Brodsky, 2017

Impresión con tintas de pigmentos duros sobre papel Hahnemülhe

60 x 90 cm.

Edición 7 + A/P

Black and white archival photograph © Wolfgang Kunz, 1968, intervened with handwritten texts by Marcelo Brodsky, 2017

Print with hard pigment inks on Hahnemühle paper

23,6 x 35,4 in.

Edition 7 + A/P

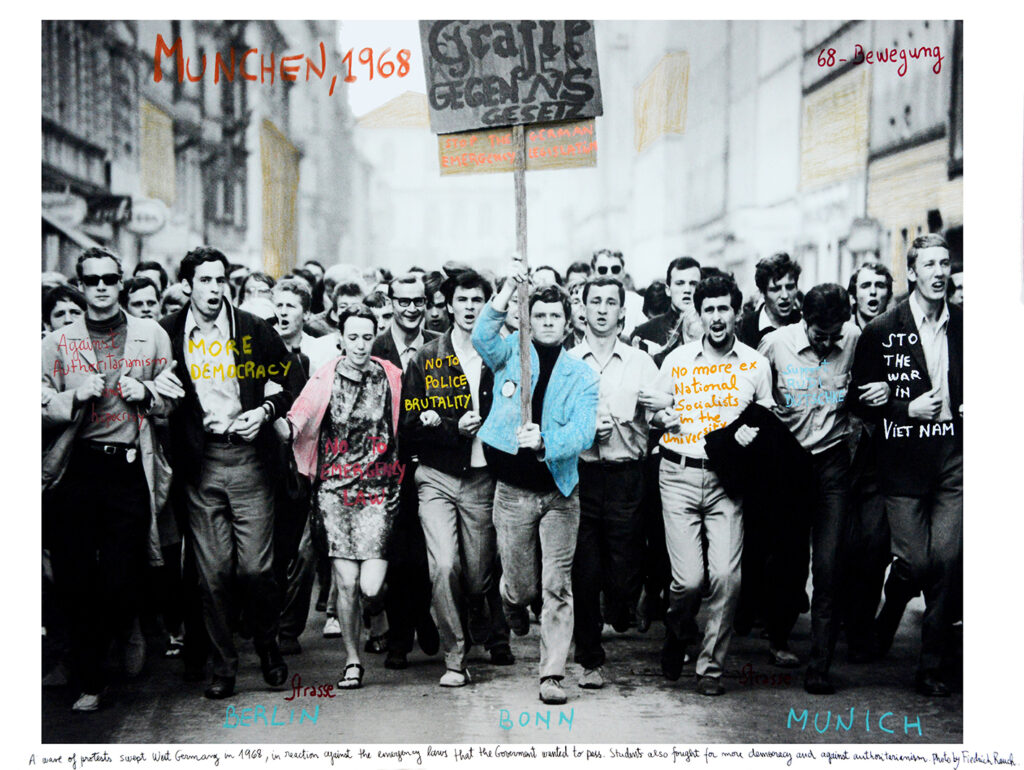

Fotografía de archivo blanco y negro © Friedrich Rauch, 1968, intervenida con textos a mano por Marcelo Brodsky, 2015

Impresión con tintas de pigmentos duros sobre papel Hahnemülhe

60 x 90 cm.

Edición 7 + A/P

Black and white archival photograph © Friedrich Rauch, 1968, intervened with handwritten texts by Marcelo Brodsky, 2015

Print with hard pigment inks on Hahnemühle paper

23,6 x 35,4 in.

Edition 7 + A/P

Fotografía de archivo blanco y negro © Cor Jaring, intervenida con textos a mano por Marcelo Brodsky, 2018

Impresión con tintas de pigmentos duros sobre papel Hahnemülhe

60 x 90 cm.

Edición 7 + A/P

Black and white archival photograph © Cor Jaring,

intervened with handwritten texts by Marcelo Brodsky, 2018

Print with hard pigment inks on Hahnemühle paper

23,6 x 35,4 in.

Edition 7 + A/P

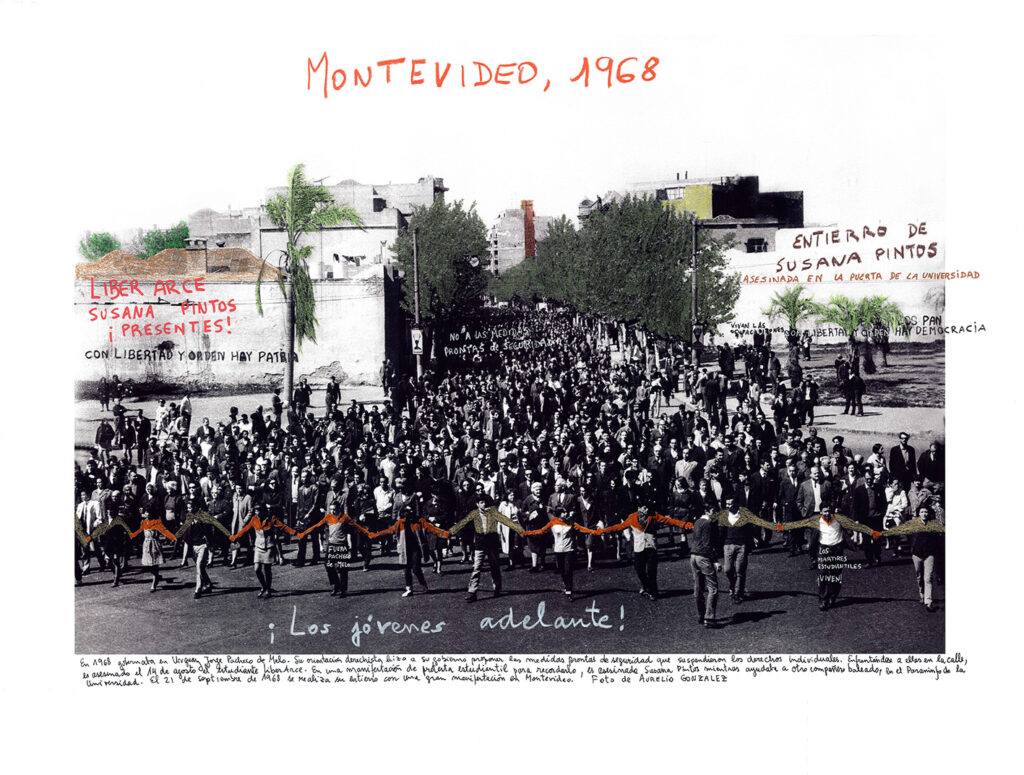

Fotografía de archivo blanco y negro © Aurelio González, 1968, intervenida con textos a mano por Marcelo Brodsky, 2016

Impresión con tintas de pigmentos duros sobre papel Hahnemülhe

60 x 90 cm.

Edición 7 + A/P

Black and white archival photograph © Aurelio González, 1968, intervened with handwritten texts by Marcelo Brodsky, 2016

Print with hard pigment inks on Hahnemühle paper

23,6 x 35,4 in.

Edition 7 + A/P

Fotografía de archivo blanco y negro © Boris Spremo, 1968, intervenida con textos a mano por Marcelo Brodsky, 2017

Impresión con tintas de pigmentos duros sobre papel Hahnemülhe

60 x 90 cm.

Edición 7 + A/P

Black and white archival photograph © Boris Spremo, 1968, intervened with handwritten texts by Marcelo Brodsky, 2017

Print with hard pigment inks on Hahnemühle paper

23,6 x 35,4 in.

Edition 7 + A/P

Fotografía de archivo blanco y negro © Akg Imagenes, Wenceslas Sq, Prague 1968, intervenida con textos a mano por Marcelo Brodsky, 2015

Impresión con tintas de pigmentos duros sobre papel Hahnemülhe

60 x 90 cm.

Edición 7 + A/P

Black and white archival photograph © Akg Imagenes, Wenceslas Sq, Prague, 1968, intervened with handwritten texts by Marcelo Brodsky, 2015

Print with hard pigment inks on Hahnemühle paper

23,6 x 35,4 in.

Edition 7 + A/P

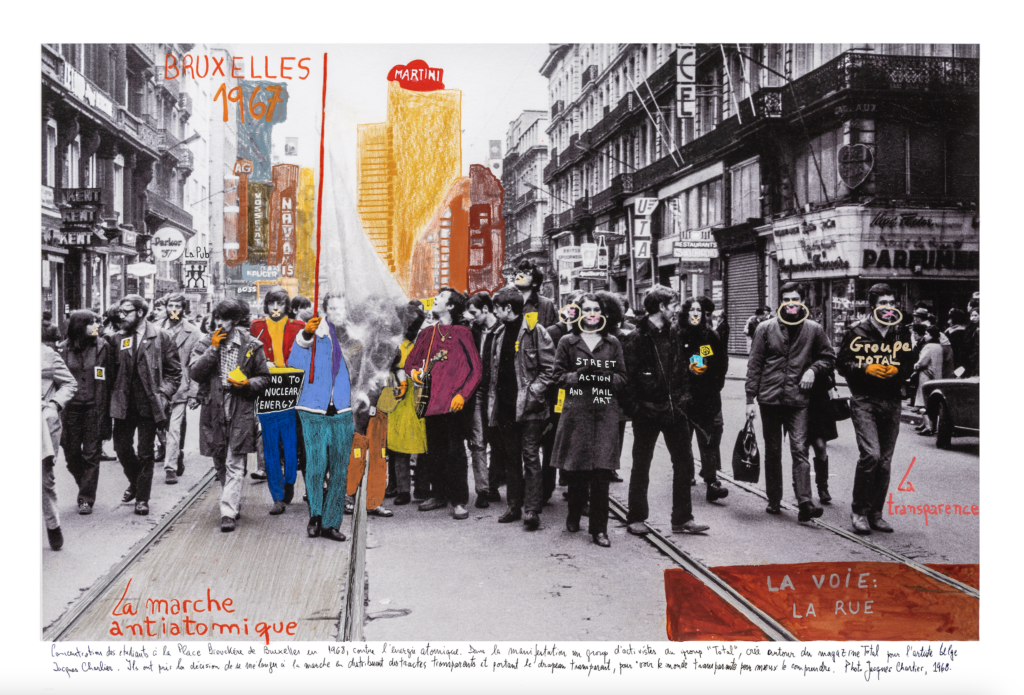

Fotografía de archivo blanco y negro © Spaarnestad Collection National Archief, 1967, intervenida con textos a mano por Marcelo Brodsky, 2016

Impresión con tintas de pigmentos duros sobre papel Hahnemülhe

60 x 90 cm.

Edición 7 + A/P

Black and white archival photograph

© Spaarnestad Collection National Archief,1967,

intervened with handwritten texts by Marcelo Brodsky, 2016

Print with hard pigment inks on Hahnemühle paper

23,6 x 35,4 in.

Edition 7 + A/P

Fotografía de archivo blanco y negro © Paris Police Archive, 1968, intervenida con textos a mano por Marcelo Brodsky, 2014

Impresión inkjet con tintas de pigmentos duros sobre papel algodón Hahnemühle

90 x 60 cm

Edición 7 + A/P

Black and white archival photograph © Paris Police Archive, 1968,

hand-intervened with colors & written texts by Marcelo Brodsky, 2014

Inkjet print with hard pigment ink on Hahnemühle cotton paper

35,4 x 23,6 in

Edition 7 + A/P

Fotografía de archivo blanco y negro © Paris Police Archive, 1968, intervenida con textos a mano por Marcelo Brodsky, 2014

Impresión con tintas de pigmentos duros sobre papel Hahnemülhe

60 x 90 cm.

Edición 7 + A/P

Black and white archival photograph © Paris Police Archive, 1968, intervened with handwritten texts by Marcelo Brodsky, 2014

Print with hard pigment inks on Hahnemühle paper

23,6 x 35,4 in.

Edition 7 + A/P

Fotografía de archivo blanco y negro © Ladislav Bielik, 1968, intervenida con textos a mano por Marcelo Brodsky, 2016

Impresión con tintas de pigmentos duros sobre papel Hahnemülhe

60 x 90 cm.

Edición 7 + A/P

Black and white archival photograph © Ladislav Bielik, 1968, intervened with handwritten texts by Marcelo Brodsky, 2016

Print with hard pigment inks on Hahnemühle paper

23,6 x 35,4 in.

Edition 7 + A/P

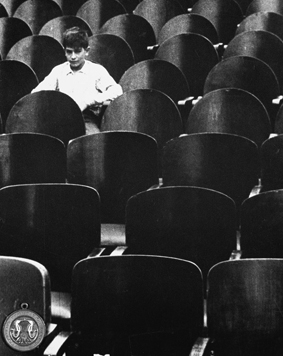

Fotografía de archivo en blanco y negro de © Marcelo Brodsky, 1968, intervenida con textos

a mano por el artista, 2014

60 x 90 cm

Edición 5 + A/P

Black and white archival photograph by © Marcelo Brodsky, 1968, intervened with handwritten

texts by the artist, 2014

23,6 x 35,4 in

Edition 5 + A/P

Fotografía de archivo blanco y negro © Agencia Jornal do Brasil, 1968,

intervenida con textos a mano por Marcelo Brodsky, 2015

Impresión inkjet con tintas de pigmentos duros sobre papel algodón Hahnemühle

90 x 60 cm

Edición 7 + A/P

Black and white archival photograph © Agencia Jornal do Brasil, 1968,

hand-intervened with colors & written texts by Marcelo Brodsky, 2015

Inkjet print with hard pigment ink on Hahnemühle cotton paper

35,4 x 23,6 in

Edition 7 + A/P

Fotografía de archivo blanco y negro © Robert Harding P.L., 1968, intervenida con textos a mano por Marcelo Brodsky, 2017

Impresión con tintas de pigmentos duros sobre papel Hahnemülhe

60 x 90 cm.

Edición 7 + A/P

Black and white archival photograph © Robert Harding P.L., 1968, intervened with handwritten texts by Marcelo Brodsky, 2017

Print with hard pigment inks on Hahnemühle paper

23,6 x 35,4 in.

Edition 7 + A/P

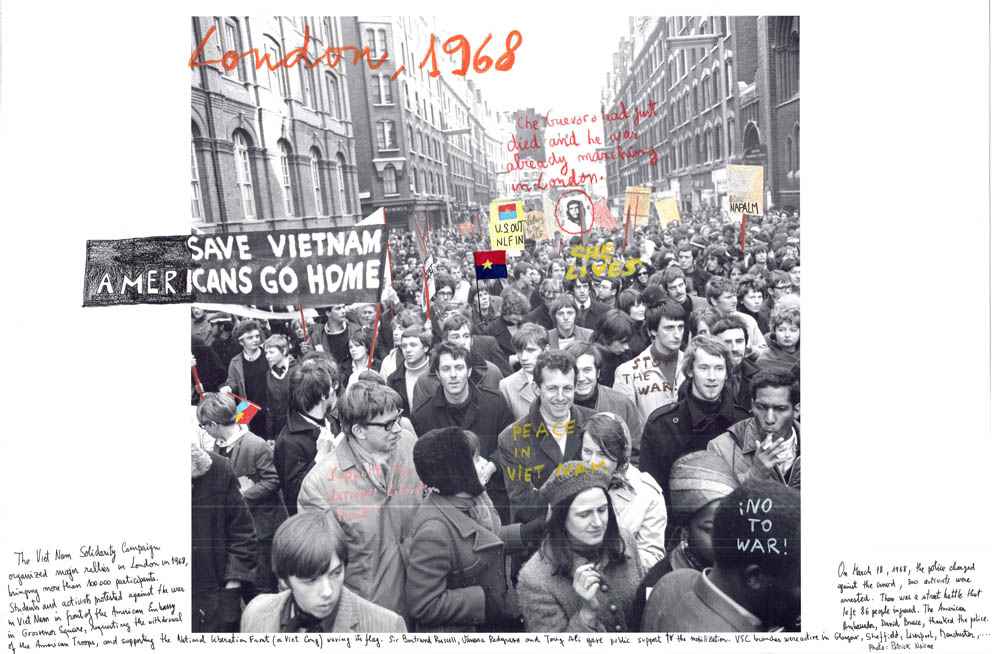

Fotografía de archivo blanco y negro © Patrick Nairne, 1968, intervenida con textos a mano por Marcelo Brodsky, 2015

Impresión con tintas de pigmentos duros sobre papel Hahnemülhe

60 x 90 cm.

Edición 7 + A/P

Black and white archival photograph © Patrick Nairne, 1968, intervened with handwritten texts by Marcelo Brodsky, 2015

Print with hard pigment inks on Hahnemühle paper

23,6 x 35,4 in.

Edition 7 + A/P

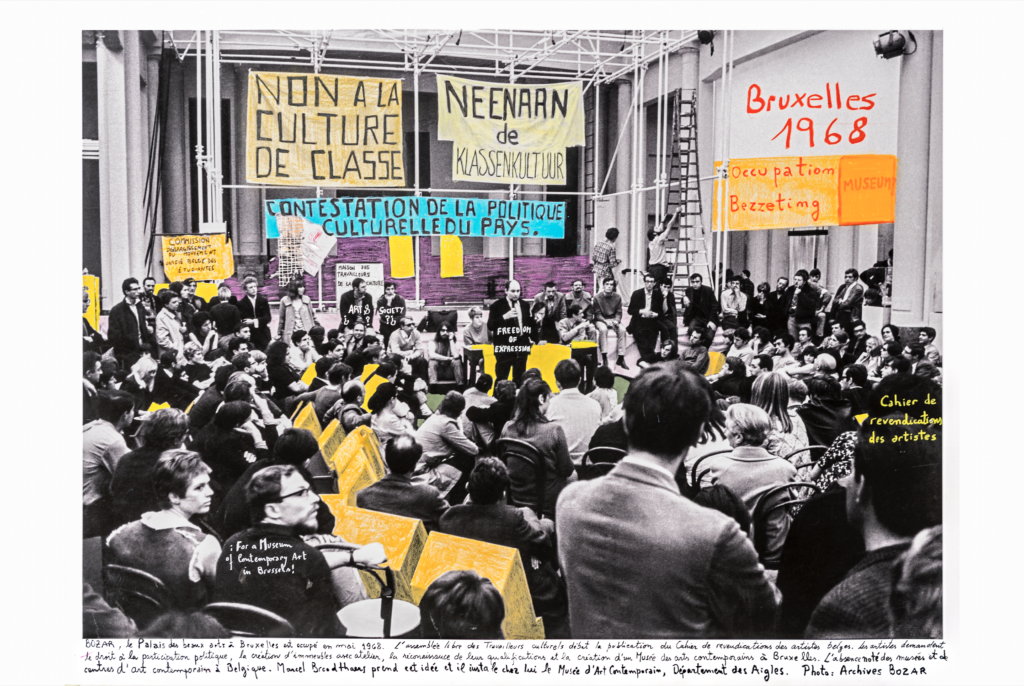

Fotografía de archivo blanco y negro © Archives Bozar, 1968, intervenida con textos a mano por Marcelo Brodsky, 2018

Impresión con tintas de pigmentos duros sobre papel Hahnemülhe

60 x 90 cm.

Edición 7 + A/P

Black and white archival photograph © Archives Bozar, 1968 intervened with handwritten texts by Marcelo Brodsky, 2018

Print with hard pigment inks on Hahnemühle paper

23,6 x 35,4 in.

Edition 7 + A/P

Fotografía de archivo blanco y negro © Agence France Presse, 1968, intervenida con textos a mano por Marcelo Brodsky, 2017

Impresión con tintas de pigmentos duros sobre papel Hahnemülhe

60 x 90 cm.

Edición 7 + A/P

Black and white archival photograph © Agence France Presse, 1968, intervened with handwritten texts by Marcelo Brodsky, 2017

Print with hard pigment inks on Hahnemühle paper

23,6 x 35,4 in.

Edition 7 + A/P

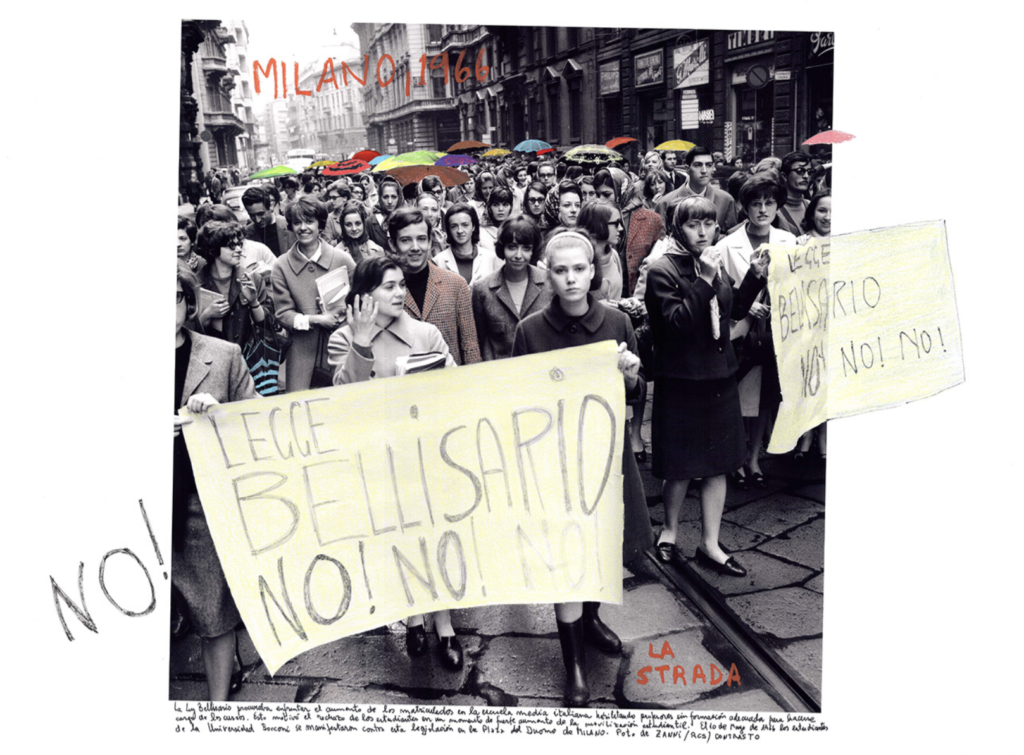

Fotografía de archivo blanco y negro © Zanni-RCS-Constrasto, 1966, intervenida con textos a mano por Marcelo Brodsky, 2016

Impresión con tintas de pigmentos duros sobre papel Hahnemülhe

60 x 90 cm.

Edición 7 + A/P

Black and white archival photograph © Zanni-RCS-Constrasto, 1966, intervened with handwritten texts by Marcelo Brodsky, 2016

Print with hard pigment inks on Hahnemühle paper

23,6 x 35,4 in.

Edition 7 + A/P

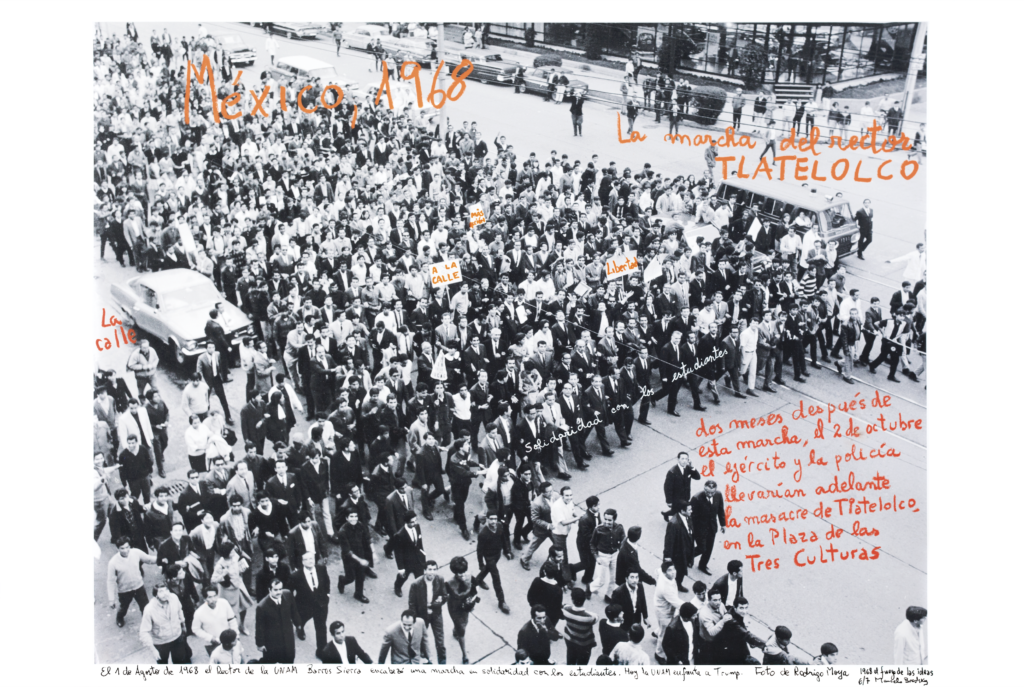

Fotografía de archivo blanco y negro © Rodrigo Moya 1968, intervenida con textos a mano por Marcelo Brodsky, 2014

Impresión con tintas de pigmentos duros sobre papel Hahnemülhe

60 x 90 cm.

Edición 7 + A/P

Black and white archival photograph © Rodrigo Moya 1968, intervened with handwritten texts by Marcelo Brodsky, 2014

Print with hard pigment inks on Hahnemühle paper

23,6 x 35,4 in.

Edition 7 + A/P

Fotografía de archivo blanco y negro © Jorge Silva/Cine Mestizo, 1968, intervenida con textos a mano por Marcelo Brodsky, 2015

Impresión con tintas de pigmentos duros sobre papel Hahnemülhe

45 x 60 cm.

Edición 7 + A/P

Black and white archival photograph © Jorge Silva/Cine Mestizo, 1968, intervened with handwritten texts by Marcelo Brodsky, 2015

Print with hard pigment inks on Hahnemühle paper

17,7 x 23,6 in.

Edition 7 + A/P

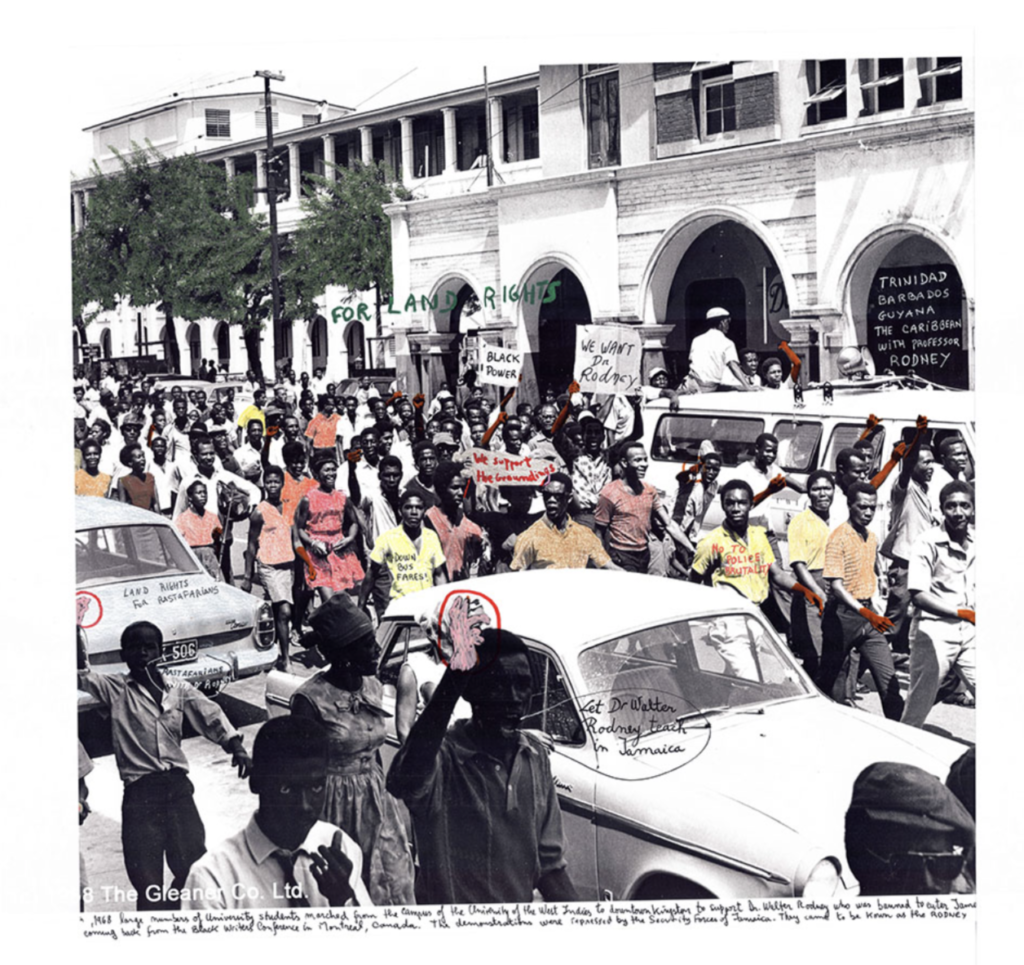

Fotografía de archivo en blanco y negro de © The Gleaner Co. Ltd., 1968, intervenida con textos

a mano por Marcelo Brodsky, 2016

60 x 90 cm

Edición 5 + A/P

Black and white archival photograph by © The Gleaner Co. Ltd., 1968, intervened with handwritten

texts by Marcelo Brodsky, 2016,

23,6 x 35,4 in

Edition 5 + A/P

Fotografía de archivo blanco y negro © Evandro Teixera, 1968,

intervenida con textos a mano por Marcelo Brodsky, 2015

Impresión inkjet con tintas de pigmentos duros sobre papel algodón Hahnemühle

90 x 60 cm

Edición 5 + A/P

Black and white archival photograph © Evandro Teixera, 1968,

hand-intervened with colors & written texts by Marcelo Brodsky, 2015

Inkjet print with hard pigment ink on Hahnemühle cotton paper

35,4 x 23,6 in

Edition 5 + A/P

Fotografía de archivo blanco y negro © Stevan Kragujevic, Colección del Museo de Yugoslavia, 1968, intervenida con textos a mano por Marcelo Brodsky, 2014-2017

Impresión con tintas de pigmentos duros sobre papel Hahnemülhe

60 x 90 cm.

Edición 7 + A/P

Black and white archival photograph © Stevan Kragujevic, Museum of Yugoslavia Photo Collection, 1968, intervened with handwritten texts by Marcelo Brodsky, 2014-2017

Print with hard pigment inks on Hahnemühle paper

23,6 x 35,4 in.

Edition 7 + A/P

Fotografía de archivo en B&N © Carlos Guimaraes, intervenida con textos a mano por Marcelo Brodsky, 2017

Impresión con tintas de pigmentos duros sobre papel Hahnemülhe

Medidas variables

Edición 7 + 2AP

Black and white archival photograph © Carlos Guimaraes,

intervened with handwritten texts by Marcelo Brodsky, 2017

Print with hard pigment inks on Hahnemühle paper

23,6 x 35,4 in

Edition 7 + 2AP

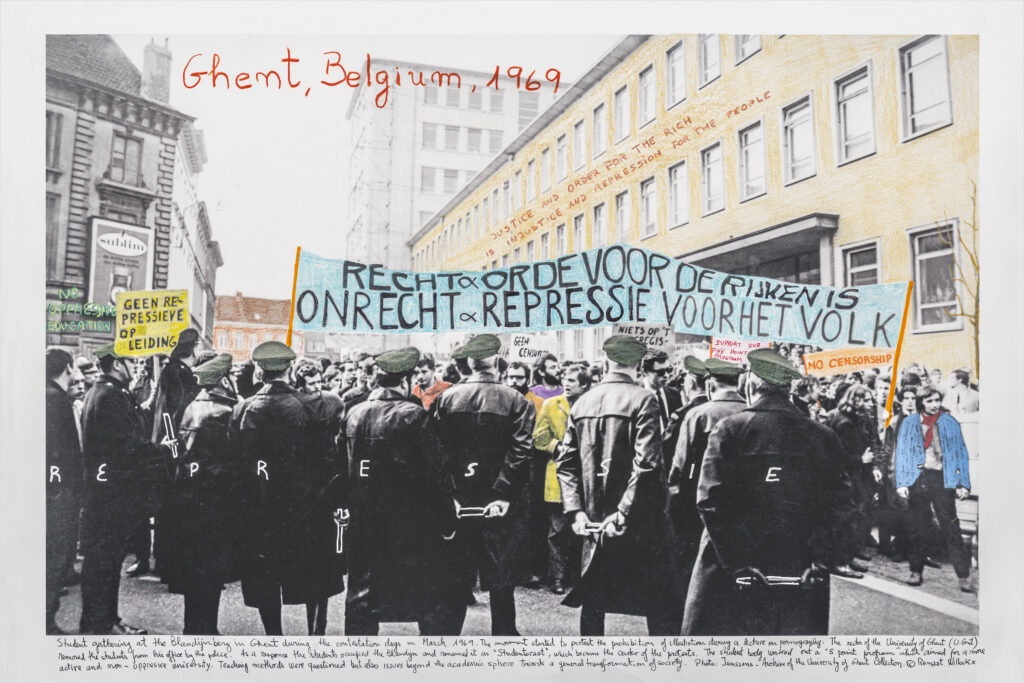

Fotografía de archivo blanco y negro © Renaat Willockx, Janssens, Archivo de la colección de la Universidad de Ghent, 1969, intervenida con textos a mano por Marcelo Brodsky, 2014-2017

Impresión con tintas de pigmentos duros sobre papel Hahnemülhe

60 x 90 cm.

Edición 7 + A/P

Black and white archival photograph © Renaat Willockx, Janssens, Archive of the University of Ghent Collection, 1969, intervened with handwritten texts by Marcelo Brodsky, 2014-2017

Print with hard pigment inks on Hahnemühle paper

23,6 x 35,4 in.

Edition 7 + A/P

Fotografía de archivo blanco y negro © Archives Bozar, 1968,

intervenida con textos a mano por Marcelo Brodsky, 2018

Impresión con tintas de pigmentos duros sobre papel Hahnemühle

60 x 90 cm.

Edición 7 + 2 A/P

Black and white archival photograph © Archives Bozar, 1968

intervened with handwritten texts by Marcelo Brodsky, 2018

Print with hard pigment inks on Hahnemühle paper

23,6 x 35,4 in

Edition 7 + 2 A/P

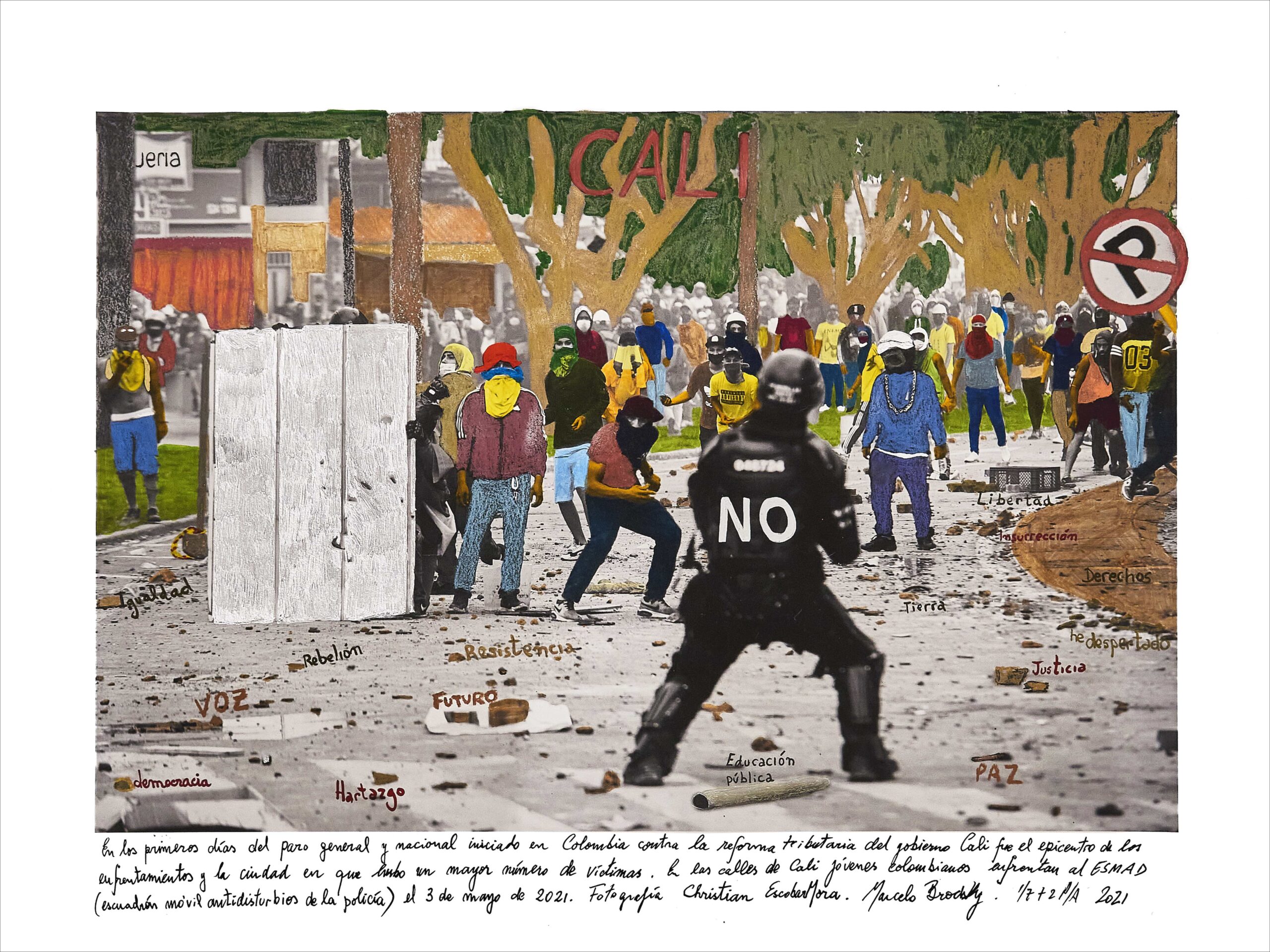

De la serie Paro Nacional 2021, Colombia

Fotografía

Fotografía de archivo blanco y negro © Federico Rios Escobar, 2021 intervenida con textos y pintada a mano con crayón y acuarela por Marcelo Brodsky, 2021 Impresión con tintas de pigmentos duros sobre papel Hahnemülhe

45 x 60 cm.

Edición 7 + 2 A/P

From the series National Strike 2021, Colombia

Photograph

Black and white archival photograph © Federico Rios Escobar, 2021 intervened with handwritten texts and painted with crayon and watercolor by Marcelo Brodsky, 2021

Print with hard pigment inks on Hahnemühle paper

17.7 x 23.6 in.

Edition 7 + 2 A/P

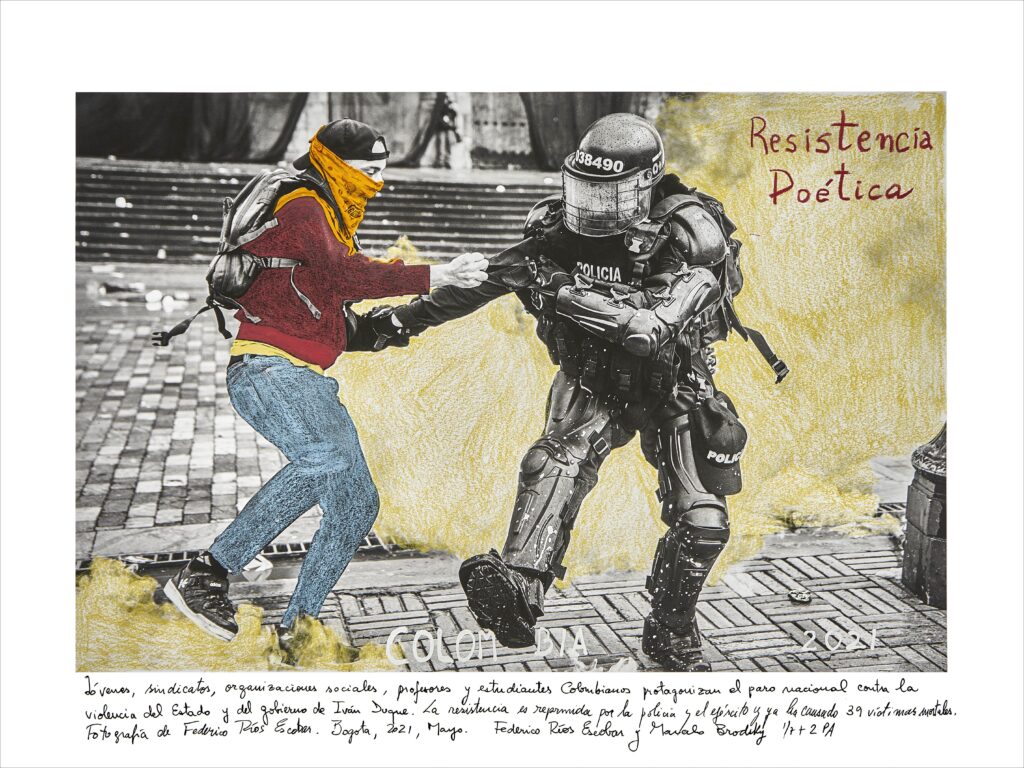

De la serie Paro Nacional 2021, Colombia

Fotografía

Fotografía de archivo blanco y negro © Federico Rios Escobar, 2021 intervenida con textos y pintada a mano con crayón y acuarela por Marcelo Brodsky, 2021 Impresión con tintas de pigmentos duros sobre papel Hahnemülhe

45 x 60 cm.

Edición 7 + 2 A/P

From the series National Strike 2021, Colombia

Photograph

Black and white archival photograph © Federico Rios Escobar, 2021 intervened with handwritten texts and painted with crayon and watercolor by Marcelo Brodsky, 2021

Print with hard pigment inks on Hahnemühle paper

17.7 x 23.6 in.

Edition 7 + 2 A/P

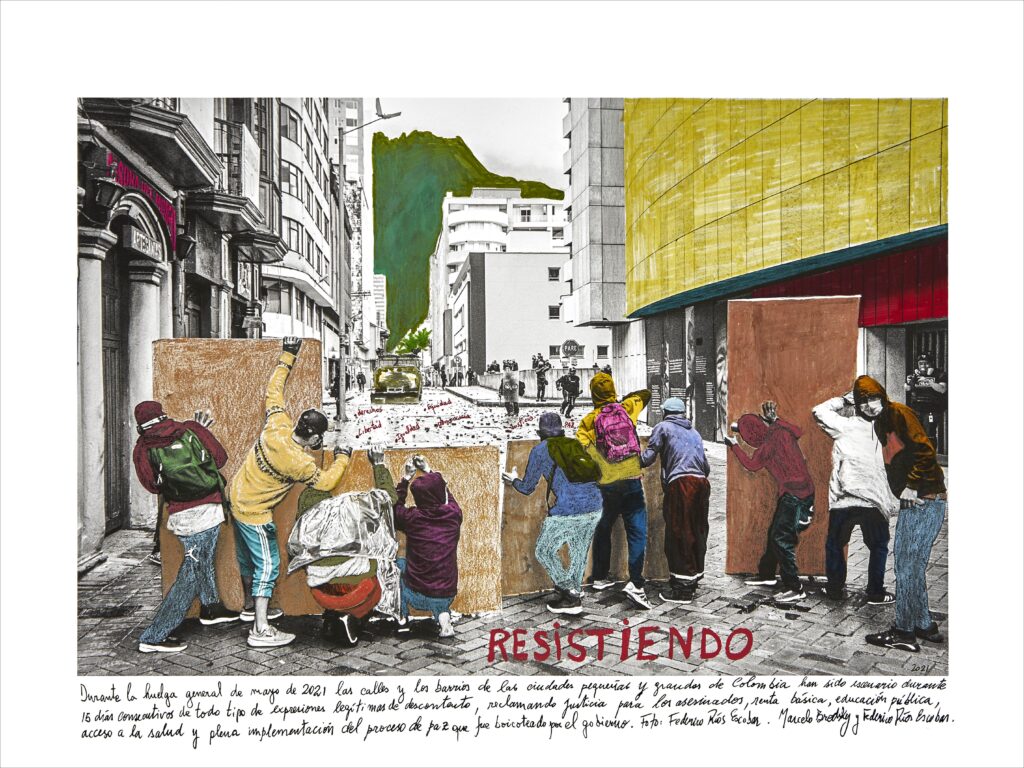

De la serie Paro Nacional 2021, Colombia

Fotografía

Fotografía de archivo blanco y negro © Federico Rios Escobar, 2021 intervenida con textos y pintada a mano con crayón y acuarela por Marcelo Brodsky, 2021 Impresión con tintas de pigmentos duros sobre papel Hahnemülhe

45 x 60 cm.

Edición 7 + 2 A/P

From the series National Strike 2021, Colombia

Photograph

Black and white archival photograph © Federico Rios Escobar, 2021 intervened with handwritten texts and painted with crayon and watercolor by Marcelo Brodsky, 2021

Print with hard pigment inks on Hahnemühle paper

17.7 x 23.6 in.

Edition 7 + 2 A/P

De la serie Paro Nacional 2021, Colombia

Fotografía

Fotografía de archivo blanco y negro © Federico Rios Escobar, 2021 intervenida con textos y pintada a mano con crayón y acuarela por Marcelo Brodsky, 2021 Impresión con tintas de pigmentos duros sobre papel Hahnemülhe

45 x 60 cm.

Edición 7 + 2 A/P

From the series National Strike 2021, Colombia

Photograph

Black and white archival photograph © Federico Rios Escobar, 2021 intervened with handwritten texts and painted with crayon and watercolor by Marcelo Brodsky, 2021

Print with hard pigment inks on Hahnemühle paper

17.7 x 23.6 in.

Edition 7 + 2 A/P

De la serie Paro Nacional 2021, Colombia

Fotografía

Fotografía de archivo blanco y negro © Federico Rios Escobar, 2021 intervenida con textos y pintada a mano con crayón y acuarela por Marcelo Brodsky, 2021 Impresión con tintas de pigmentos duros sobre papel Hahnemülhe

45 x 60 cm.

Edición 7 + 2 A/P

From the series National Strike 2021, Colombia

Photograph

Black and white archival photograph © Federico Rios Escobar, 2021 intervened with handwritten texts and painted with crayon and watercolor by Marcelo Brodsky, 2021

Print with hard pigment inks on Hahnemühle paper

17.7 x 23.6 in.

Edition 7 + 2 A/P

El proyecto de Marcelo Brodsky ofrece una narrativa subjetiva en la que la fotografía actúa como memoria. Comprometido con la lucha por defender causas sociales estrictamente relacionadas con los derechos de la humanidad.

La fotografía en su obra es un testigo, una suerte de “servicio documental” al ser trabajadas combinando material de archivo y documentación que el artista inscribe sobre las imágenes condensando experiencias traumáticas, vestigios de vivencias ligadas al horror y el exilio. Marcas, notas, colores, el tono lacónico, archivístico, de la información alude al discurso impersonal de la historia; la caligrafía, desprolija y urgida, invaden las fotografías señalando, destacando, acentuando las faltas, los vacíos provocados por aquellos que ya no están, o los reclamos de una sociedad.

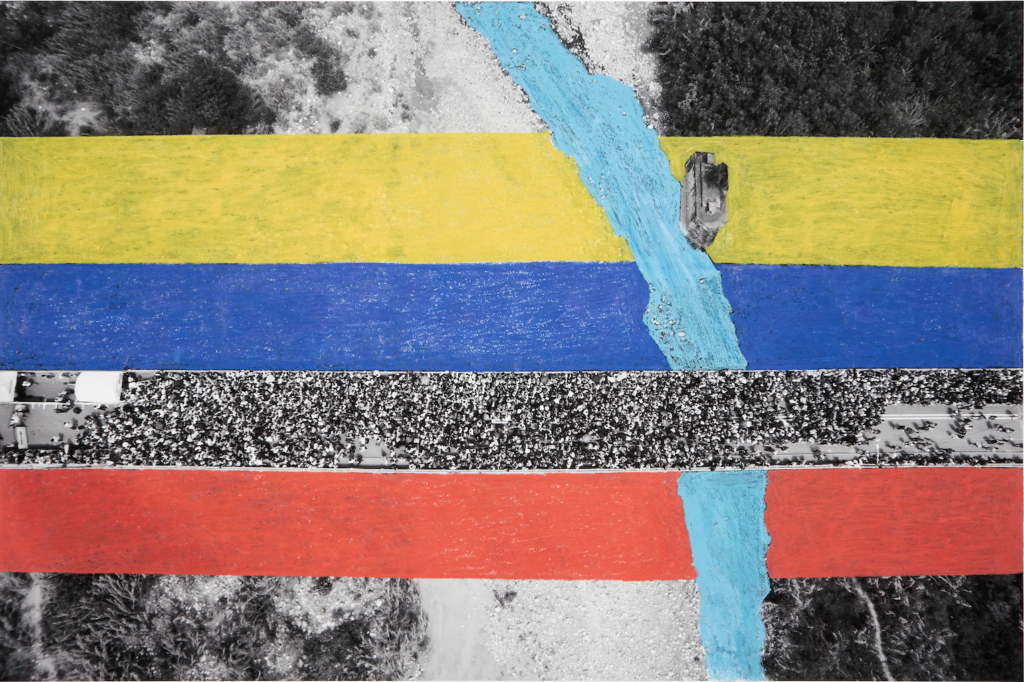

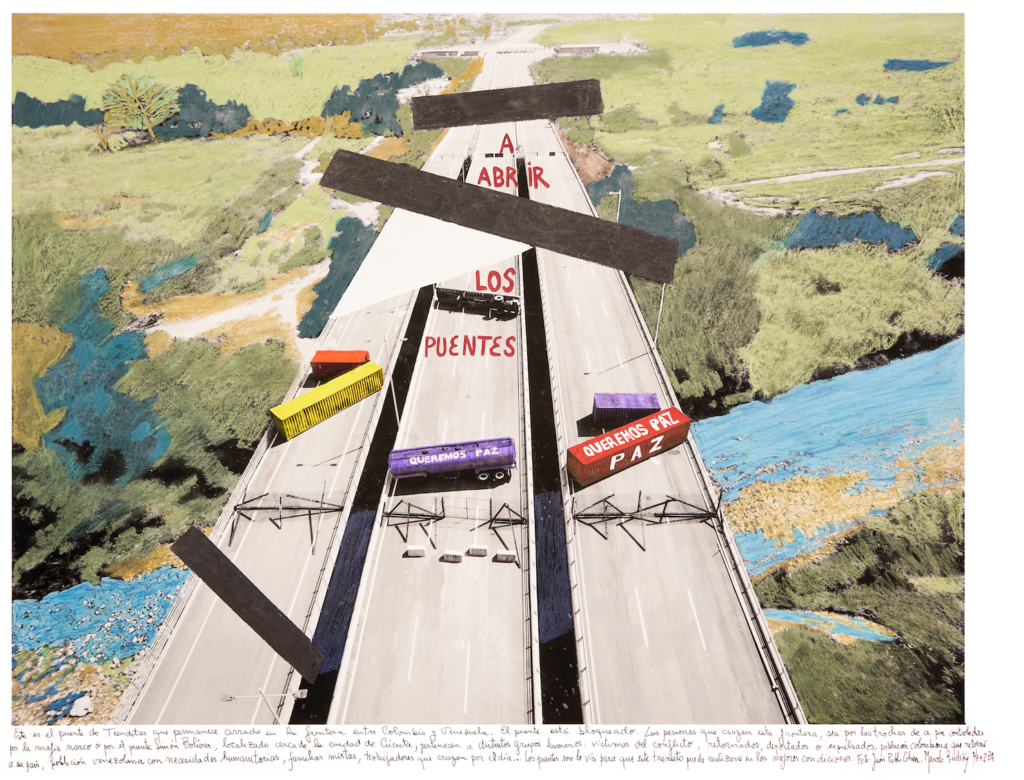

“…Las relaciones entre el arte y la violencia señalan el itinerario vital de una cultura diversa, rica y sorprendente, gestada por un país cuyo color y cuyo ritmo embelesan y encandilan. La paz soñada, imaginada y negociada es negada con cada nueva víctima. Los jóvenes ocupan las calles y resisten, aguantan y plantean preguntas sin respuesta a un aparato de poder soberbio que muestra sus rendijas.

Las fronteras, porosas, donde transitan las familias que fueron de un único país, son punto de fricción y de reencuentro. No hay diferencias reales, las familias son las mismas, siempre vivieron a ambos lados del borde. Los puentes al abrirse permiten el flujo natural de lo imparable…”

Marcelo Brodsky sobre Abrir los puentes & Paro Nacional, 2021

De la serie Abrir los puentes, Cúcuta – Juntos Aparte

Fotografía

Fotografía de archivo blanco y negro © Juan Pablo Cohen, 2019 intervenida con textos y pintada a mano con crayón y acuarela por Marcelo Brodsky, 2019 – 2020

64,5 x 90 cm.

Edición 7 + 2 A/P

From the series Open the bridges, Cúcuta – Together Apart

Photograph

Black and white archival photograph by © Juan Pablo Cohen intervened with handwritten texts & painted with crayon and watercolor by Marcelo Brodsky 2019 – 2020

Print with hard pigment inks on Hahnemühle paper

25.3 x 35.4 in.

Edition 7 + 2 A/P

De la serie Abrir los puentes, Cúcuta – Juntos Aparte

Fotografía

Fotografía de archivo blanco y negro © Juan Pablo Cohen, 2019 intervenida con textos y pintada a mano con crayón y acuarela por Marcelo Brodsky, 2019

Impresión con tintas de pigmentos duros sobre papel Hahnemülhe

64,5 x 90 cm.

Edición 7 + 2 A/P

From the series Open the bridges, Cúcuta – Together Apart

Photograph

Black and white archival photograph by © Juan Pablo Cohen intervened with handwritten texts & painted with crayon and watercolor by Marcelo Brodsky 2019

Print with hard pigment inks on Hahnemühle paper

25.3 x 35.4 in.

Edition 7 + 2 A/P

De la serie Abrir los puentes, Cúcuta – Juntos Aparte

Fotografía

Fotografía de archivo blanco y negro © Juan Pablo Cohen, 2019 intervenida con textos y pintada a mano con crayón y acuarela por Marcelo Brodsky, 2019

Impresión con tintas de pigmentos duros sobre papel Hahnemülhe

64,5 x 90 cm.

Edición 7 + 2 A/P

From the series Open the bridges, Cúcuta – Together Apart

Photograph

Black and white archival photograph by © Juan Pablo Cohen intervened with handwritten texts & painted with crayon and watercolor by Marcelo Brodsky 2019

Print with hard pigment inks on Hahnemühle paper

25.3 x 35.4 in.

Edition 7 + 2 A/P

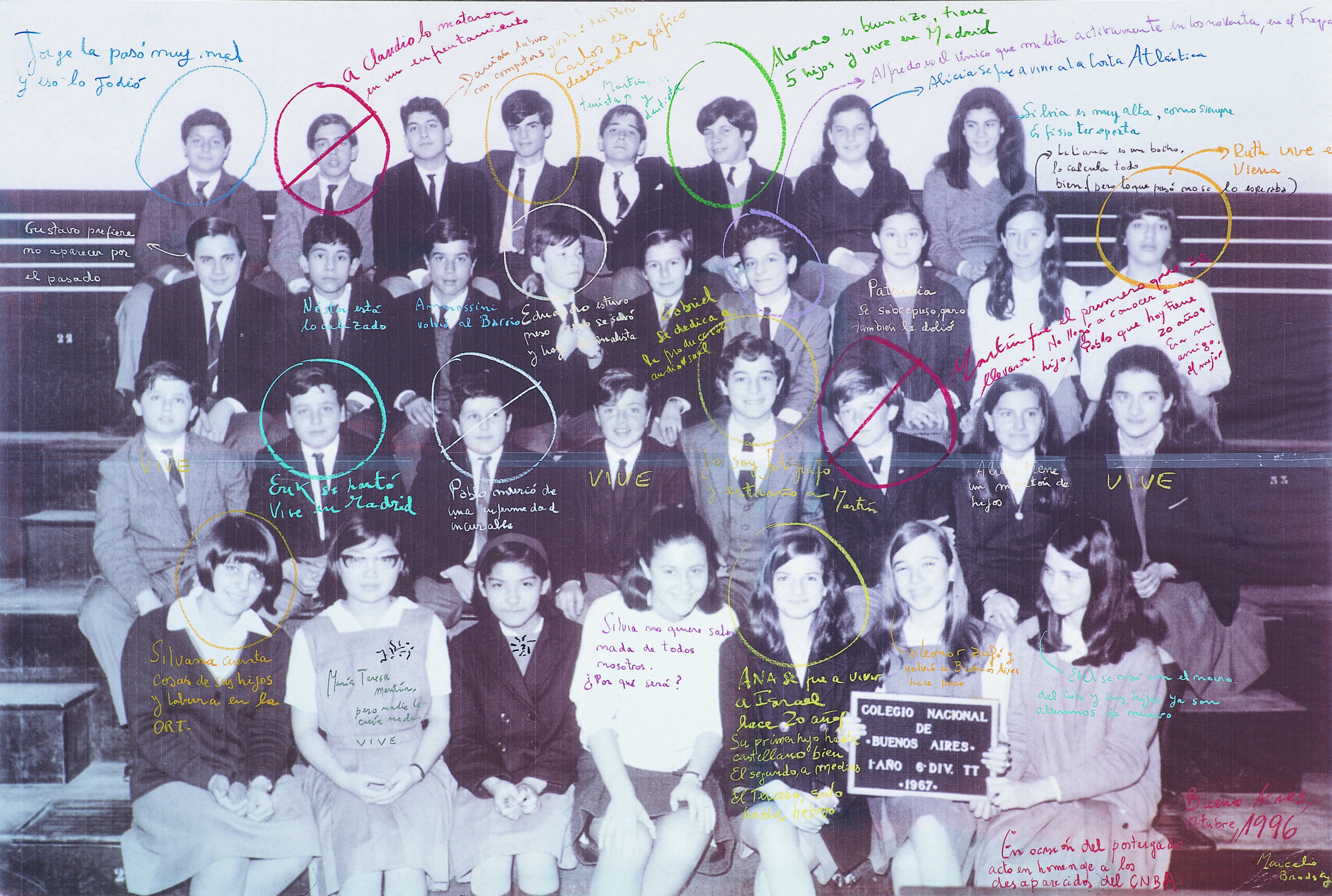

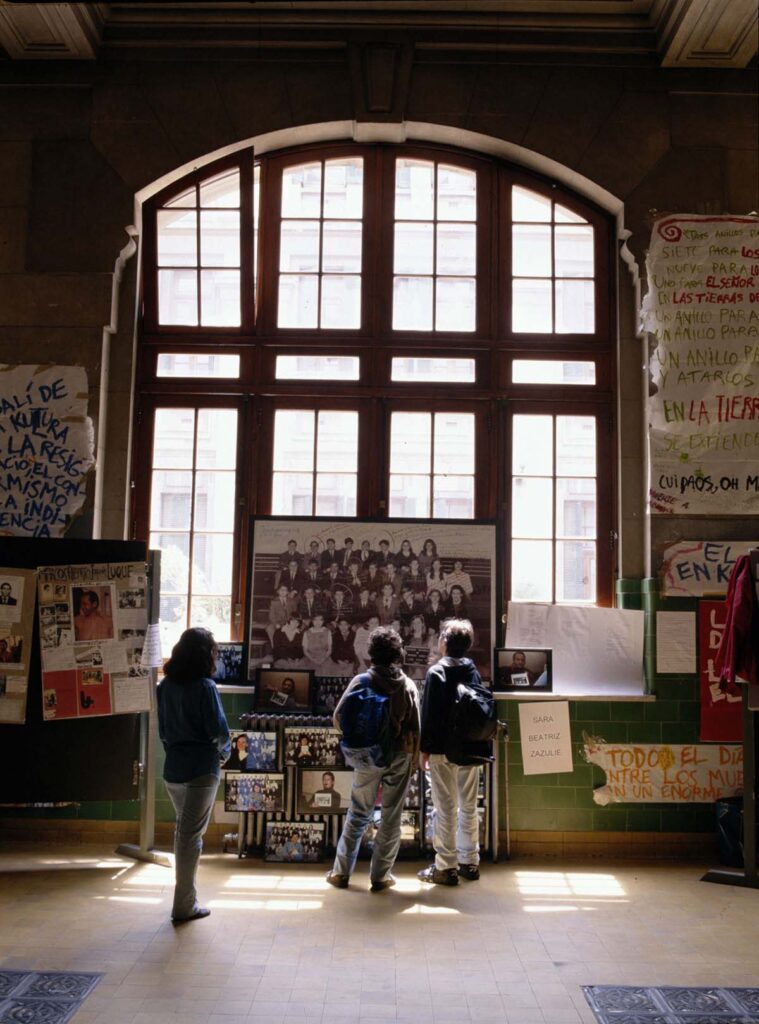

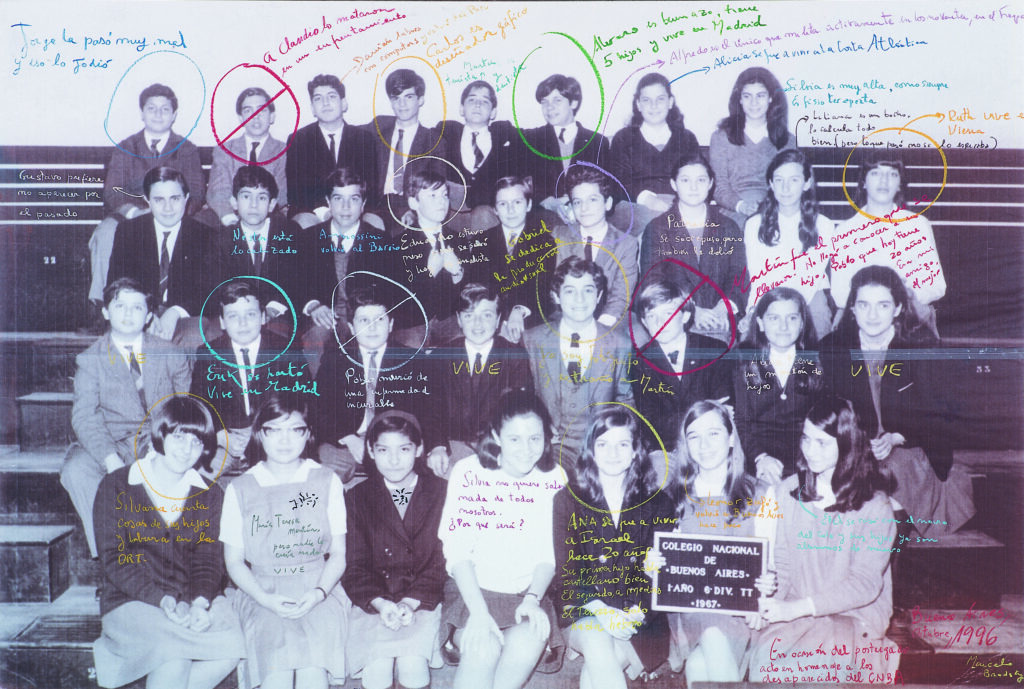

Buena Memoria se centra en los tiempos de dictadura Argentina durante la cual el estado torturó y ejecutó sistemáticamente miles de ciudadanos, conocidos como los desaparecidos. Liderados por el general Jorge Rafael Videla, la dictadura militar tomó el poder en 1976 y mantuvo su gobierno opresivo hasta 1983. Al regresar de su exilio en España a su tierra natal a la edad de cuarenta años, Brodsky utilizó fotografías familiares como punto de partida para un cuerpo de obras que tratan de comunicar el trauma de la experiencia vivida.

La obra 1er Año, 6ta División, 1967 es una reproducción a gran escala de una fotografía de su clase tomada en ese mismo año en el Colegio Nacional de Buenos Aires. En la superficie, Brodsky ha inscrito marcas y notas en colores brillantes que detallan el destino de sus compañeros de clase. Mientras que algunos se habían casado o emigrado, otros fueron “desaparecidos”. La obra entera de Marcelo Brodsky está atravesada por relaciones constitutivas entre la imagen y la palabra. En Buena Memoria el tono lacónico, archivístico, de la información alude al discurso impersonal de la historia; la caligrafía, desprolija y urgida, a la memoria, que solo puede revelarse en la presencia de un cuerpo.

Como observó Walter Benjamín, la huella fotográfica es opaca hasta que se escribe su sentido, y esta escritura revela el futuro (aún siniestro) del pasado que ella ha apresado. El proyecto más amplio al cual esta obra pertenece, continúa este proceso de reformulación de los materiales existentes. Otras obras de esta serie utilizan las instantáneas del álbum de fotos familiares del artista para centrarse en su hermano menor Fernando, desaparecido a la edad de veintidós años en 1979. Presionando el pasado contra el presente, estas obras de figuras “fantasmales” parecieran anticipar su propio futuro. Al trasponer materiales vernáculos familiares y el testimonio personal en la esfera pública, el artista otorga una oportunidad para que otros puedan identificarse y conmoverse, permitiendo la comprensión de sucesos lejanos. Brodsky explora la capacidad de la fotografía para proporcionar un espacio de meditación entre la memoria privada y las historias colectivas.

De la serie Buena Memoria

Fotografía

Impresión Inkjet sobre papel de algodón

60 x 50 cm.

From the Good Memory series

Photography

Inkjet print on cotton paper

23,6 x 19,6 in.

De la serie Buena Memoria

Fotografía

Impresión Inkjet sobre papel de algodón

60 x 50 cm.

From the Good Memory series

Photography

Inkjet print on cotton paper

23,6 x 19,6 in.

De la serie Buena Memoria

Fotografía

Impresión Inkjet sobre papel de algodón

60 x 50 cm.

From the Good Memory series

Photography

Inkjet print on cotton paper

23,6 x 19,6 in.

De la serie Buena Memoria

Copia: 2013

Fotografía intervenida

Gigantografía intervenida por el artista

Papel de algodón Hahnemüle

Photo Rag 308 g.

127 x 185 cm.

Edición 5 + A/P

From the Good Memory series

Print: 2013

Intervened photography

Gigant print intervened by the artist

Cotton paper Hahnemüle Photo Rag 308 g.

50 x 72,8 in.

Edition 5 + A/P

De la serie Buena Memoria

Fotografía

Gelatina de plata sobre papel fibra

69 x 55 cm.

From the Good Memory series

Photography

Gelatin silver print on fiber paper

27,2 x 21,7 in.

De la serie Buena Memoria

Fotografía

Impresión Inkjet sobre papel de algodón

50 x 60 cm.

From the Good Memory series

Photography

Inkjet print on cotton paper

19,7 x 23,6 in.

De la serie Buena Memoria

Nando, mi hermano

Fotografía

Gelatina de plata sobre papel fibra

55,5 x 56 cm.

From the Good Memory series

Photography

Gelatin silver print on fiber paper

21,9 x 22 in.

De la serie Buena Memoria

Fotografía

Gelatina de plata sobre papel fibra

51 x 56 cm.

From the Good Memory series

Photography

Gelatin silver print on fiber paper

20 x 22 in.

La atención sobre los derechos humanos, en cuya defensa Brodsky trabaja activamente, ha abierto nuevos caminos para el papel político y público de las artes visuales. Nexo – continuidad de su primer libro Buena Memoria- es un ensayo fotográfico que pretende formar parte de un diálogo abierto de voces y puntos de vista acerca de las prolongadas consecuencias que ha tenido el terrorismo de Estado y que combina de modo ecléctico la fotografía directa, la fotografía de archivo, textos, instalaciones, mármoles y video.

Gran parte de su nueva obra gira en torno de la memoria de los desaparecidos y vincula los efectos del terrorismo de Estado con el pasado, al ligarla al tropo del Holocausto y con el futuro, asociándola con episodios trágicos más próximos- el atentado a la Amia en 1994. Las obras de Nexo aluden más que a la memoria oficial, a la memoria vivida, localizada en cuerpos individuales, en su experiencia y en su dolor, comprometiendo a la vez la memoria colectiva, política o generacional.

“Manel fue mi maestro de fotografía durante mi exilio en Barcelona, a comienzos de los ochenta. Fue un modelo muy positivo y estimulante de producción visual, fiel a sus obsesiones, serio en el laboratorio, exigente y divertido, moderno y distante, por momentos, en otros amigo cercano, noctámbulo, fotógrafo de la noche, un tipo muy influyente en los fotógrafos de su generación. Manel se ocupó más de sus fotos que de promocionar su trabajo. Durante un tiempo estuvo haciendo fotografía de moda, y estuvo en parte alejado del circuito del arte, del que sin embargo es miembro pleno por su obra. Cuando viví en Madrid, no lo ví. Unos años después de regresar a Argentina, fui con Marcos y Res a Arles, en 1996 y lo ví. Tengo una foto de Julio Grimblatt que recoge el momento en que le muestro las primeras fotos de Buena Memoria, cuando aún no se había expuesto más que en el Colegio. Nos vimos, intercambiamos direcciones, un contacto.

En 2005 fui a presentar Memoria en Construcción en Barcelona y lo invité y nos vimos ya con más tiempo, y nos tomamos algo y nos contamos de la vida. Fue un encuentro muy lindo. Yo ya fotógrafo pleno, como él. Nos planteamos armar algo juntos, y fuimos pensando mostrar paralelamente fotos de nuestra obra hasta que llegamos a la conclusión que era mejor mostrar algo hecho ahora, y ahí fueron apareciendo las correspondencias como idea. Manel ya había tenido un diálogo de fotos por poemas con dos poetas catalanes, que habían participado de un reciente catálogo suyo. Ahí armamos la correspondencia, en la que llevamos casi dos años, y tenemos 34 fotos. La hemos mostrado primero en la sala Cruce de Madrid, luego en la galería VVV de Bs As y también en la galería Fidel Balaguer de Barcelona.”

Marcelo Brodsky

There are photos that literally become burnt into the collective consciousness of a generation or nation. And there are also those images which fail to achieve iconic status, even though they have so much to say about an era and those shaping it, images supplied by photographers from around the world to agencies of which today only a tiny minority ever get published. In an era in which there is a seemingly endless flood of digital images, many events that seem to be unfolding in our world are already forgotten the following day. The often-evoked collective memory? As full of holes as a Swiss cheese and also apparently of very limited capacity. What do today’s forty-somethings know about the ’68 movement today? Thirty-somethings? Or even twenty-somethings? Mostly these are narratives which can be told through pictures; images which bring history to life and enable you to empathize with the situation of those involved; images familiar from television documentaries or school lessons; images which gradually fade from our memory over time.

This is Marcelo Brodsky’s starting point. The photographer Brodsky, human rights activist and long-time director of the Latin Stocks Latinstock photo agency, born in 1954 in Buenos Aires, has achieved a name for himself through his unconventional picture language and technique. His works hang in the great museums of the world, from the London Tate to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Here the Argentinian sometimes uses original photographs by other photojournalists as the basis for his very special vision of historical figures and scenes. Brodsky transforms photos into works of art by colouring details of oversized black-and-white prints, adding handwritten annotations or sketches to the images, highlighting certain frequently overlooked elements. He expressly explores archives, on the lookout for photos which are able to tell the stories important to him. «The first thing is to identify and sketch the relevant aspects of the image so that they are perceived more intensively by the viewer,» says Brodsky about his creative process. Above all, colour, text and drawings serve one purpose: to create or emphasize emotions.

In his work entitled 1968 – The Fire of Ideas, a highly acclaimed project, Brodsky takes this approach to the extreme. Starting with original press photos, Brodsky’s meticulous process of editing helps create completely unique works, in which the artist is clearly pursuing an objective: to enlighten, to render history comprehensible and tangible; using what he himself calls a very personal virtual visual essay. «Young people do not accept content without pictures today. History must therefore be recounted through images,» says Brodsky. Going even further, he claims: «There are young people who have no idea of what happened in 1968. Because they no longer read, they need to learn through pictures.» This explains why the focus of Brodsky’s work is the narrative, the whole picture, not the original photograph.

Marcelo Brodsky is – quite unusual in the contemporary scene – a thoroughly political artist, driven by what he personally experienced at the time of the Argentine military dictatorship. The Argentinian is seeking to pass on this knowledge, arguing for human rights, drawing attention to injustice, putting his finger in the wound. «Many of the ideas from 1968 are more interesting and true than those discussed today,» says Brodsky. But many issues become distorted and reinterpreted over time. Even photos often lose their authenticity. The internet, the social networks, the flood of images: sometimes it seems that we lack an ordering hand, an expert eye, and thus become lost in visual confusion. Quality media should actually provide this ordering of images: by selecting, weighting, commenting on and verifying pictures and messages. However, the media’s reach and revenue are in decline. In an age of Twitter and Instagram, each and every smartphone user creates an own personal reality. In the end, the hunger for fast, easily consumable news dominates. And some only believe what they wish to believe. Including untruths.

In fact, the world is in need of a greater number of enlightened individuals. More artists. More curiosity and empathy. We believe, thanks to Google, that we know every corner of the planet. But what do we Europeans really know about Latin America? Or more importantly (because more obvious) what about Africa? About the day-to-day life of the people? About politics and culture? About millions of human rights violations? About hunger and wars?

People like Marcelo Brodsky still have a lot to say. And we are curious……

He knew. And he was right. The remarkable British writer, who died ten years ago this April, lived for five decades under the Heathrow flight path in the anonymous suburban London settlement of Shepperton, but in his mind he traversed all the borders of time and space, reporting back from the vast reaches of his imagination in numerous volumes of visionary speculative fiction.

For him the ‘deep assignment’ started with his singular childhood in China under Japanese occupation, and the centrality of this experience to the material and psychic topographies of his writing reveals that his life project was anything but ‘coincidental’. However, it is not only in form and content that such conjunctions reveal themselves. The concern here is about supportive circulation, about networks of sympathy and committed association. For assignments can also occur in the passage of a work through the world, in the encounters it prompts and receives, in the doors and windows it opens, in the thresholds it crosses, for both writer and reader, artist and viewer. In such a light, what might appear on casual examination to be pleasurable chance reveals itself in due course – and taken alongside the accretion of subsequent details – to be anything but; to be, in fact, the working out and through of an almost ordained, even inevitable synchronicity.

Something similar occurred in my rendez-vous with first the art, and later the person of Marcelo Brodsky. In 2004, and without any prior knowledge of either the artist or the exhibition in question, I found myself in London’s Photofusion gallery, surrounded by the extraordinary experience of his Buena Memoria (www.photofusion.org/exhibitions/marcelo-brodsky/).

This affected me deeply of course, emotionally, aesthetically and politically (I had been very active in the UK Latin American solidarity movement of the 1980s and 1990s) but the timing of my viewing was also hugely informed by the extensive planning and pre-production for ‘Here Is Where We Meet’, a six week London season I curated, which celebrated the work in multiple media of the late, great, much missed and internationally celebrated writer John Berger (http://johnberger.org/).

Passionately committed to global struggles for justice, and with a huge admiration for Latin American writers, artists and filmmakers, Berger was clearly a kindred spirit. I bought the exhibition catalogue at once and, when I was next in Paris to see John, I gave it to him. We looked at it together, I told him about the installation. He was very moved by it. So it goes.

Life – and events – moved on; the season happened (a year later and almost exactly to the dates of Brodsky’s show). It was a great success, led to Berger donating his extensive archive to the British Library, and to his renewed status in UK cultural life (he had left London in the early 1960s to live in Europe, a conscious internationalist). He continued to publish important books until his death, aged 90, in January 2017.

Two years later, a friend Gideon Mendel, the renowned South African documentary photographer, resident close by in London, mentioned that he was collaborating with Brodsky on treatments of his own photographs of resistance to Apartheid and that Brodsky was soon to attend the London Art Fair to present his ‘Fire of Ideas’ series.

At the same time I received a message from Sikh poet Amarjit Chandan, also living in the city and a close friend of Berger’s. He and Brodsky had recently been in parallel contact, and Amarjit revealed that John had asked him to work on a shared response to Buena Memoria all the way back in 2004, prompted by the catalogue I had given Berger, but which it turned out he had then misplaced. The intended piece did not happen but letters retained by Amarjit confirmed once more that Berger valued Brodsky’s images and intervention. So it goes.

Finally, therefore, 15 years after the exhibition that prompted this sequence of ‘call and response’, echo and intention, in January 2019 we all met in London, the holding space for these stories and navigations. We raised glasses to the benign ways of the world, to John’s memory and to onward creative dialogues.

Why write about this publicly? Is it not really only of interest to those involved? Perhaps, but at the same time I believe it also illustrates, or rather embodies, even proposes a way we might wish to live in the world. At times of crisis, the question of ‘what matters’ is thrown into sharp relief, along with how to identify priority and need, structures of necessity, in what one does or can do, especially if one’s skills are not clearly of immediate and undeniable practical application (the medical being among the most obvious).

Correspondences like those described above can help enormously in confirming the modest potential usefulness of one’s actions (an idea central to Berger’s sense of how his own writing should operate). They suggest that forms of advocacy, on whatever scale, are indivisible from the nature of what is being advocated; in other words, that works are less a product and far more a process. They are active, and activating. Once made, and all the more so if motivated by progressive desires for the common good, they enter into a systemic dialogue with the possible. They themselves then become repeatedly ‘possible’ in how they might engender welcome and fruitful reactions, and thus continue to move forwards.

And we with them, through a society and a period that lay siege to reason, beauty and dreaming; and yet, without such works – fragile, fierce, passionate, provocative, elegiac and endlessly engaged – where would we be…

In the dark times,

will there also be singing?

Yes, there will be singing,

about the dark times.

– Bertolt Brecht

Gareth Evans is an event and film producer, writer and editor. He is the Adjunct Moving Image Curator at Whitechapel Gallery, London, As well as the season mentioned, he has commissioned and published two original books by John Berger, and wrote a poem for him that gave its title to Berger’s 2007 essay collection Hold Everything Dear.

Du darfst nicht sitzen und alles auf dich zukommen lassen. Du darfst dich vor allen Dingen nicht dem Gedanken hingeben, daß Mächtige über Dir sind, die doch alles bestimmen.

You must not sit and let that everything comes to you. Above all, you must not surrender to the thought that powerful people above determine everything.

Peter Weiss

In 1981, in a passage of the interview given to Heinz Ludwig Arnold, German artist and writer Peter Weiss summarized the fundamental observation conveyed by his three-volume novel Die Ästhetik des Widerstands (The Aesthetic of Resistance, 1975–81) as follows: at any given moment in history―and, at that time, also in many Latin American countries ruled by dictatorships―people have always demonstrated a powerful drive to resist injustice and limitations to their freedom and, moved by a strange principle hope (“einen merkwürdigen Prinzip Hoffnung”), rise up in protest against coercive governments at the risk of their own lives and liberty. Weiss’s book is a dramatized historical account of the proletarian resistance against fascism in the Europe of the late 1930s and into the Second World War. His message, however, is still relevant today and strongly resonates in Marcelo Brodsky’s latest art project, The Poetics of Resistance.

In his books, Weiss, departing from a description of the gigantomachy frieze of the Pergamon Altar in Berlin and its symbolic representation of the constant and ubiquitous presence of revolt and suffering in human history, put the emphasis primarily on aesthetics, that is on the visual experience of art, its educational potential for the viewer and the necessary role it plays in any revolution. Brodsky, on the other hand, addresses the notion of resistance first and foremost from the perspective of a poetic exercise. ‘Poetics’ is the theory of poetry and literary discourse, its origins in Western philosophy can be traced back to Aristoteles and his homonymous treatise (De Poetica, in the Latin translation). While the primary focus of poetics is set on the different components of the text, their interaction and the resulting effects they exert on the reader, poetics does not pertain only to poetry in verses but to any work of art which uses language. Interweaving text, image and colour, Brodsky’s “intervened photographs”, as he defines them, exemplify this theoretical approach and become a poetic instrument of social awareness.

Brodsky is conscious of the power of both images and words. Born in Argentina in 1954, over the past five decades he has progressively developed a unique poetics based on the interaction of, mostly journalistic and archival, photographs and written annotations to achieve his objective: to activate personal and collective memory to communicate a message of resistance that may connect people across time and space. Working at the crossroads between visual arts, poetry and human rights activism, Brodsky’s practice is rooted in his personal history and direct dramatic experience of State-sponsored terror in Argentina. During the Argentine Military Dictatorship (1976–83), his best friend Martín Bercovich and his younger brother Fernando were abducted and disappeared in 1976 and 1979 respectively, a traumatic event which prompted the artist to go into exile in Barcelona, where he lived until the period of military dictatorship in Argentina ended and democracy was restored.

Brodsky, who has owned and directed a photographic agency for many years in Spain and Latin America, does not use the media merely as a source of inspiration. Rather, he turns the media itself into an artwork. Selecting photographs collected in documentary archives around the world, the artist manipulates them: by adding handwritten comments and highlighting meaningful details with the help of bright and vivid colours, he stimulates a dialogue between the pre-existing narratives conveyed by the original sources and his own interpretation of those texts and images. Brodsky has been employing this strategy since 1996, when he realized Buena Memoria (Good Memory), one of his most celebrated and iconic works to date. Departing from an enlarged black and white group photograph of his class taken at school in 1967, at the age of thirteen, Brodsky intervened it with annotations, drew circles, arrows and crosses to visually trace to date the destiny of the children portrayed on the image. His comments read like succinct epitaphs celebrating heroic patriots: “Claudio was killed fighting the military”, “Pablo died of an incurable disease”, “Martín is the first one they disappeared”, “Ana went to live in Israel”… This modus operandi is still at the base of the artist’s most recent projects, but over the years it has greatly gained in strength, both in style and in the variety of its contents.

Brodsky can lean on a long standing tradition in Argentina, the inception of which dates back to the second half of the 1960s, when media theory based on the work of Marshal McLuhan, Umberto Eco and Roland Barthes was taught at the Instituto Torcuato di Tella in Buenos Aires. These theories inspired several vanguard projects like the legendary “Tucumán arde” (Tucuman is Burning) as well as an entire generation of artists slightly older than Brodsky – such as Marta Minujín, Eduardo Costa, Raúl Escar and Roberto Jacoby – to use media not just as a tool for transferring information but also as a critical “device for the exaltation and construction of alternative realities”. Brodsky’s work is an ongoing reflection on the way in which media affects reality (and its memory), and contributes to the shaping of national cultural identity through the diffusion of heavy edited self-portraits of the society it depicts. But his work is also an investigation of how media can be transformed into an instrument capable of creating awareness of such patterns, while instigating discussion among present and future generations. As he explains: “Photography’s potential to record imperceptible changes and the passage of time in each person’s face might be extended exponentially to register human experience, artistic events and performative actions that draw a sort of map of collective action, creating a socio-political itinerary of gestures, dramatizations, positions and provocations. It would be a kind of social aura, a collective imaginary.”

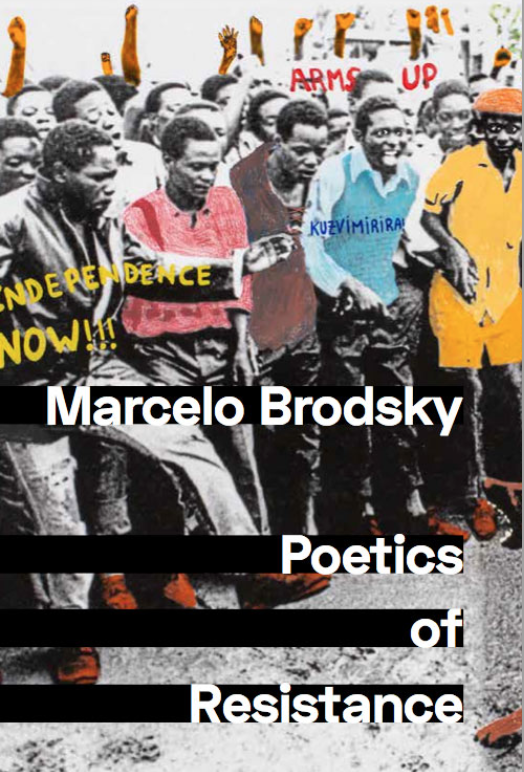

The Poetics of Resistance reunites two major groups of works created by the artist between 2014 and 2019: 1968. The Fire of Ideas, composed of 55 intervened archival photographs devoted to the international mobilisations and protests of workers and students in 1968, and the series of 20 images centred on the decolonisation process in Africa and its progressive transition to independence during the second half of the 20th century. The project also encompasses two further and still ongoing lines of inquiry by Brodsky, devoted to the anti-Franco resistance in Spain and to today’s burning question of migrants and refugees―in which, for the very first time, the artist engages in a reflection on contemporary issues. Adding annotations and clearly non-impartial captions, Brodsky recounts historic episodes of major turmoil and revolution: from the anti-Vietnam War protests in London to the struggle for the independence of Congo and the rebellions caused by the murder of his anti-colonialist Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba in 1961; from the 1968-revolts of the student unions in Dakar requesting more political freedom from President Léopold Senghor to the violent state of emergency in South Africa during the anti-Apartheid struggle in the 1980s. Departing from black and white photographs documenting social and political events around the globe, Brodsky’s plastic and textual artistic interventions aim at engaging the viewer, regardless of where he or she lives and whatever his or her background is, not just in a conceptual and aloof reflection on those historical moments and histories of resistance, but in a responsive and personal identification with their protagonists. What is the relation between the bloody repression of the student protests in 1968 pre-Olympic Mexico and the disappearance of 43 students in Ayotzinapa on September 26, 2014? Is there a connection between the current migrants’ crisis in Europe and Africa’s colonial past? These and similar questions are raised by Brodsky’s works and addressed to the viewer.

Brodsky is particularly committed to speaking to younger generations. He knows very well that, in the time of social media and instant communication, this can happen effectively mainly through images and short messages. “Professionals of the image like me”, he points out, have the “responsibility” to positively shape the way we make use of them in our society.

As a human rights activist―he is one of the co-founders of the Parque de la memoria in Buenos Aires―Brodsky believes that his artistic practice can help to effect positive change by promoting awareness in people, worldwide. His work is an empowering manifestation of that strange and absurd, but nonetheless strident hope referred to by Peter Weiss, that is the common denominator of past and present human action and desire, and which prompts the urge to act and to bring about change that is at the hearth of every gesture of resistance. Participating in the “global discourse about historical trauma”, Brodsky’s intervened photographs are “memory art” with a strong impact on our present and future: intensely visualizing past traumas, they counteract the fatalism that too often inhibits us from resisting, taking action and contributing to revolutions big and small which take place daily, around the world.

Marcelo Brodsky, artista y activista de los derechos humanos, trabaja con imágenes y documentos de eventos específico para investigar ampliamente los problemas y acciones sociales, políticos e históricos. Quiere que los espectadores sean conscientes de momentos históricos, algunos de los cuales lo formaron a él, a su familia y a muchos de sus amigos. Más específicamente, y como muchos de los de su generación en Argentina, Brodsky fue atacado durante la dictadura militar, que durante siete años de reinado del terror, fue responsable de la tortura y muerte de entre 10.000 y 30.000 argentinos, incluyendo al propio hermano menor del artista, Fernando. Brodsky escapa de la mano de los militares y vive en el exilio hasta que la dictadura finaliza en 1983. Aunque que las experiencias personales instigan y dan forma a sus impulsos artísticos, educar al público con la esperanza de prevenir a otros de tal terror, es su motivación más fuerte.

Para hacer que los momentos elegidos y sus consecuencias sean accesibles al espectador, Brodsky se acerca al material de diversas maneras. Constantemente su arte nos muestra un profundo entendimiento del potencial poder de las fotografías, tanto al momento de su creación como noticias y, para algunos, su vida subsecuente en publicaciones y memorias. Por décadas, Brodsky fue dueño y director de una agencia de fotografías en Latinoamérica. Su éxito dependió en parte de su conciencia sobre qué fotografías atraerían a un mayor público internacional. Él también comprende cómo utilizar las secuencias de imágenes, ya que la percepción de una simple imagen cambia cuando es emparentada o secuenciada con otras. También entiende y emplea textos en concierto con las imágenes para dirigir las percepciones del espectador, incluso cuando las palabras son aparentemente neutrales. Apasionado y determinado, Brodsky no tiene intenciones de ser neutral.

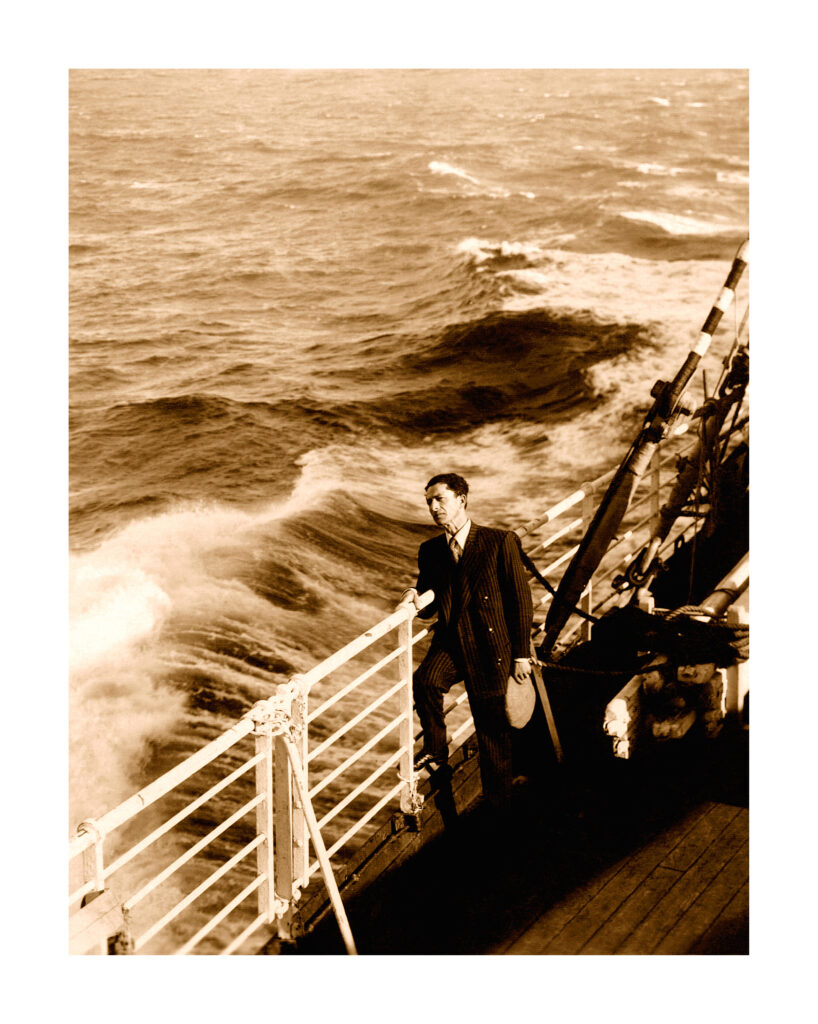

Aprende a fotografiar durante su exilio en España e incluye en esta exhibición fotografías tomadas en aquel primer año en soledad. Incluso entonces, él amplia el contexto de un autorretrato aparentemente inocente, haciendo una referencia a su propia ejecución parado sobre la pared de la plaza San Felipe Neri en Barcelona, donde el General Francisco Franco disparó a patriotas Republicanos durante la Guerra Civil Española. Algunas veces, él emplea fotografías de otras personas, como las películas de 8mm de su padre, donde sus hijos jugaban a la guerra con arcos y flechas, mucho antes de que la “Guerra sucia” o sus horribles consecuencias fueran imaginables. Puesta en el contexto de los otros trabajos, esta pieza inocente es redireccionada desde un dulce recuerdo de juegos de la infancia hacia la separación de los hermanos luego de que Fernando fuera secuestrado y desaparecido por la dictadura militar en 1979.

En otros trabajos que incorporan fotografías ajenas, ha sido siempre muy cuidadoso de tener la licencia de los derechos. El acceso a esas imágenes le permite hacer paralelismos entre eventos internacionales interrelacionados.

El trabajo más famoso de Brodsky es Buena Memoria, creado en 1996, pero tomado de una fotografía de 1967, de su clase en el Colegio Nacional de Buenos Aires. Redimensionándola y escribiendo textos sobre las figuras, comprime fuertemente el tiempo entre aquel entonces y ahora. Sobre los cuerpos y caras de los adolescentes, las palabras identifican quiénes fueron secuestrados y asesinados, quiénes partieron al exilio, quienes quedaron mentalmente dañados por la junta militar y quiénes viven vidas que aparentemente no fueron tocadas.

En otros dos trabajos, Brodsky ancla la historia Argentina con la de otros países. “I Pray with my feet” muestra imágenes de dos importantes rabinos, ambos conocidos por ser grandes defensores de los derechos civiles. El Rabino Abraham Joshua Herschel fue un estimado teólogo y profesor en el Seminario Teológico Judío en Nueva York. El Rabino Marshall T. Meyer fue estudiante y secretario personal de Herschel antes de trasladarse a la Argentina en 1959. Brodsky une el rol activo de Herschel en las marchas por los derechos civiles de los años sesentas en Estados Unidos con la constante crítica de Meyer al gobierno Argentino, hablando por los desaparecidos y consolando a sus familias durante la Guerra Sucia.

En “1968, el fuego de las ideas” Brodsky nuevamente muestra estudiantes y liga eventos en Argentina con aquellos que sucedían en el mundo, en la turbulencia social a finales de los sesentas.

Los manifestantes estadounidenses participaron de la Marcha de los Pobres en Washington, concebida por Martin Luther King unos meses antes de su asesinato; manifestantes en Londres en contra de la Guerra de Vietnam. En Bogotá, México, Córdoba, Río de Janeiro y San Pablo, trabajadores y estudiantes hacían campaña en contra de los regímenes militares y otros tipos de estructuras gubernamentales. Son mostrados con los brazos unidos, flameando banderas y pancartas, promoviendo acciones callejeras masivas para reclamar por sus derechos. La pieza también incluye extractos de discursos de Martin Luther King, el Che Guevara, Daniel Cohn Bendir, Herbert Marcuse y Agustín Tosco, quienes con sus ideales motivaron a la mayoría de los manifestantes.

Una pancarta en la manifestación Parisina que se muestra, incluye un grito de “L’imagination au pouvoir” (la imaginación al poder). Más que un llamado a “decir la verdad en el poder” que sonaba en otras manifestaciones de la era, los Parisinos pedían por el final de todos los límites, incluso en la imaginación.

Brodsky es más práctico. No pretende liberar a la imaginación de toda restricción, sino potenciarla, utilizándola contra el poder corrupto y brutal. Tanto si nos invita a aprender y no olvidar las atrocidades del pasado, a honrar a los líderes justos o, como en su más reciente campaña, a mantener la presión en las autoridades para resolver y procesar los más recientes asesinatos en masa impunes. La causa actual es en favor de 43 estudiantes desaparecidos de Ayotzinapa, México, que desaparecieron el 26 de septiembre de 2014. Para este proyecto, Brodsky retoma el motivo de la foto de la clase, pidiéndole a estudiantes alrededor del mundo que posen en gradas sosteniendo un cartel demostrando su apoyo a la “verdad” que concierne a los estudiantes muertos o encarcelados. Él quiere a los estudiantes conscientes, tanto de los problemas como de su capacidad de protestar, y a partir de esto se ha organizado una exhibición y un libro de sus fotografías para mantener vivo el

What are revolutions, if not a fire of ideas that boils inside of us, making us dream of better lives in a fair world?

Marcelo Brodsky is a revolutionist, a human rights activist and above all he is a man who is using visual art to create an awareness of our world. In a very critical and conscious way, he investigates through images, words, and documents – specific memories that have shaped our collective history and tremendously impacted his life and family. At the forefront is the Argentine military dictatorship (1976 – 1983) and its effect on his life or better yet on his generation. It was a regime of terror ruled by a state that systematically executed and made ‘disappear’ thirty thousand citizens, including his older brother Fernando and his best friend Martin Bercovich. Fortunately, Brodsky escaped to Barcelona where lived in exile until 1984. During this time, Brodsky learned the art of photography and its power as a tool in addressing social issues with a highlight on the psychological ordeals of migrants. The products of his journey into this field are works etched with collective memory, an element, which continues to be a strong pillar in his artistic practice.

In a bid to understand his identity, Brodsky on returning to Argentina at the age of 40 embarked on a systematic investigation into his personal photo archives. It was a 1967 picture of his high school class that sparked a deep curiosity to know the fate of each person in that photograph. The encounters on his quest for truth birthed what is now his most famous work – “Buena memória” (1996). In this project, the photograph “Class Photo 1967”, is drastically enlarged and the artist meticulously identifies in handwriting, the fate of each of person – killed, missing, exiled, traumatized during the ‘dirty war’. “Los Compañeros”, forms another aspect of this poignant project. It’s a video that captures one of the most striking and emotional moments of this reunion, celebration and recognition at the Colegio Nacional de Buenos Aires. This was the first official ceremony by the school authorities, recognizing (20 years later) the 98 students who were killed during this tyrannical regime. In “Los Compañeros”, the artist alternates facial elements of his classmates with images captured during this ceremony alongside voices that call out the names of the victims. Nevertheless, after much delay due to a lethargic justice system, the perpetrators responsible for Fernando’s murder were eventually sentenced in 2017. Hence the project Buena Memória, composed of family photo albums, videos, intimate and literary records may be comprehended as a collective memorial for both the fatal victims and the living ones who have survived the most atrocious period in Argentine history.

In his art project “1968: The fire of ideas (2014-2018)” that gives the title of this exhibition, Brodsky proposes a historical revision of the ideas of the late sixties, which are still very pertinent in contemporary times. The project is now a photo-essay of 50 archival images of political upheavals of students and workers across the world. These black & white photographs are meticulously handwritten on, drawing our attention to details of strength, energy and action. A visual re-contextualization that enables a deeper understanding of the past and of the impact of these fights in our society today.

1968 was a post-war period when people (collectively) were feverously awakened for a demand of rights and fresh ideals. The streets echoed with voices yearning for change. From the most violent to the pacific demonstrations, Brodsky transports us to many of these nations – Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, United Kingdom, Mexico, USA, Uruguay, Mozambique, Portugal, France, Spain, Japan, Australia, Senegal, India and even the former Czechoslovakia, where fists were raised demanding the end of oppression. They called for an end to despotic regimes and beckoned human, social and political rights. An essay that also encompasses a sound installation with speeches given by Agustin Tosco, Che Guevara, Daniel Cohn Bendit, Herbert Marcuse, Martin Luther King and Rudi Dutschke that feed the minds of many of these protesters.

Perhaps Europe in 1968 is better known as the Paris’68 mobilizations, when demonstrations, strikes and occupations happened across the country. It also chronicles this spread to other European cities yet neglecting the similarities of those within non-western contexts. A good example is the connection between France and Senegal, with their strong legal link via the Agreements for Cooperation. Senegal for instance is known for being a “well integrated society” where many African students were enrolled in French universities while French students attended the University of Dakar. Ideas and thoughts therefore were effortlessly shared. In May 27, the Senegalese student’s association eager to gain autonomy from a neo-colonialist system incited a huge boycott to the university examinations as a revolt against France. These riots forced the then president Léopold Senghor to declare a state of emergency across the country. The strength observed in Brodsky’s image of Dakar, 1968, portraying a street occupied by thousands of shoes make us ponder about the number of people involved, not to mention the sheer violence employed across the city by the police.

The series also features new revived photos from Portugal and its former African colonies. They echo the sentiments of students under Salazar’s despotic regime, the consequences of their protests, and the gains made in the fight for Democracy in Portugal and for Independence in the African countries. A curious fact in the Portuguese context is the strategy employed by the students to overcome the tough censorship while reaching a wider audience. The National football championship was used as propaganda opportunity to express their discontent with the established system. Alongside Brodsky’s powerful imagery is the documentary of Ricardo Martins “Futebol de causas” that thoroughly unveils this mark in history, something that clearly was omitted from the four daily editions of the capital newspaper “Diário de Lisboa”.

The year of 1968 must have shaken “the world”, but it took a while to reach Australian shores as their passive disposition to new ideals, revolutions and inter-territorial pillage was unchanged – “other peoples’ problems and not ours”! Therefore, their revolutionary spirit was only fully awakened in the 70s around the tail end of the Vietnam War. After a period of loss and grief it was more than necessary to revive the nation and a new sense of multicultural identity was promoted. Pulsating with keen Australian nationalist sentiments is Marcelo Brodsky photograph of 1972 Sydney’s manifestation. At the forefront is the indigenous Australian flag followed by posters with messages that advocate for ethnic equality and land rights. More importantly, Brodsky highlights “freeland” a word that represents this new dream among Australians – an ideal that resonated and still resonates today.

The voices of other artists are very present among Marcelo Brodsky’s 1968’ Fire of Ideas’ including the period where artists and students protested against the censorship in Brazil or when the Belgian artist Marcel Broodthaers played a crucial role in the cultural protest and occupation of the Centre for Fine Arts (BOZAR) in Brussels.

These photographs of Brazil represent important events in its people´s history against the military’s despotic regime. Likewise for Argentina, as people were tortured, raped, killed and arrested. Violence against women was systematic. In one these iconic photographs, the artist captures with bright colours five actresses on the frontline of a protest – five sex idols of that time fighting for women’s rights. Brodsky employed the monochromatic style in other photographs, while focusing colour on the militant messages for democracy and culture that were carried on large banners. Cultural censorship lingers again in Brazil, citing the recent closure of the art exhibition Queermuseu – Cartografias da Diferença na Arte Brasileira for which the curator Gaudêncio Fidélis is still in court for defamatory allegations.

In the case of Brussels, artists and militants took over Bozar as a means to contest the cultural politics of the country. Marcel Broodthaers was the mediator for the requests of higher levels of arts education and a museum of modern art. The ensuing revolts serve as a muse to Brodsky, who selects three images. Off the three, two images capture moments inside Bozar, in which one shows Broodthaers speaking, while CFA’s director Paul Willems listens attentively from the corner of the image. The third image captures the 1967 “Belgian anti-atomic walk” organized by the Total’s group, outside Bozar. A participatory artistic performance where Jacques Charlier’s transparent flag was hoisted amidst the other protesters. In the ritual of protest, they have their lips crossed with band-aids while distributing transparent leaflets to bystanders.

It was also during this turmoil of 1968, that Marcel Broodthaers conceived the Musée d’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles. Subsequently, during Bozar’s manifestation he relinquished being recognised as an artist and appointed himself as the director of his own museum. Undoubtedly, this was a vital project in the debate of the role of art and the function of the museums in society.

Both Brodsky and Broodthaers share a common background in poetry and the use of word as a visual language. Similarly, both artists are skilled in the ability to foment dialogues that question hegemonic narratives. For Lisbon’s exhibition, Brodsky’s correspondence with Broodthaers’s works ( from the collection of MACBA of Barcelona) creates a new series of artworks, along the line of visual dialogue and engagement. For example, in “Project pour une conversation”(2018) while performatively interacting with Broodthaers’s film “La pluie (projet pour un texte)”(1969), he positions himself both as the observer and as an obstacle between the film’s action and the audience. Thus creating multidimensional layers of interpretation of visual languages for the viewers to interact with.

Additionally, by fragmenting the original film through the use of photography, he promotes a new conversation about the power of language through the dichotomy of the moving image and the silence created in-between each still image captured. In the film, the water relentlessly erases each word that Broodthaers writes, and he keeps writing. Similarly, Brodsky reminds us that every word and every action have power and meaning and that we should pursue our convictions. This attempt at dialogue demonstrates the role of artists as critical thinkers in society and how they can contribute to a ‘revision’ of our perception of the space of art .

Marcelo Brodsky’s works are composed of powerful and aggressive images of strength that shake us up, challenging us to participate. We are confronted by a series of questions and reinterpretations, stimulating parallels with our time, our public space, our histories, our relationships with memory and with our neighbours. On the other hand, they instigate debates around the role, necessity and contribution of the arts to create spaces of freedom. In the fiftieth anniversary of 1968 which celebrates the vindication of these revolutionary ideas, we come to realize that we are still surviving violent times – Brexit, Donald Trump, xenophobia, gynophobia, massacres, etc. The work of artists like Marcelo Brodsky can make a difference by showing that the world will not get better if we just let it be!

…para que pueda ser he de ser otro,

salir de mí, buscarme entre los otros,

los otros que no son si yo no existo,

los otros que me dan plena existencia,

no soy, no hay yo, siempre somos nosotros… Octavio Paz

1.

Si el “otro” es el primero de los dones, si es aquello que le da verdadero sentido a la existencia, entonces el diálogo es privilegio, creación compartida, posibilidad y deseo de inventar con otro un universo sin renunciar al propio rostro; es responsabilidad y a la vez juego, reflexión y provocación. En el diálogo somos lo que se da: nos damos a nosotros mismos, para mostrarle al otro que aquí estamos, que nos interesa, que lo necesitamos.

El diálogo nos permite descubrir lo que nos hace semejantes, pero también lo que nos diferencia. Es el reto máximo de aceptación, donde la tensión y las contradicciones, los acuerdos y las diferencias se resuelven en una mirada doble, en una búsqueda de a dos.

2.

El género epistolar ha puesto en escena históricamente la riqueza del diálogo. Si alguna vez convocó, en tanto género literario, el cuidado de las palabras, la caligrafía exquisita, las largas páginas de reflexiones y confesiones, hoy se ha transformado en un intercambio vertiginoso, en breves mensajes que llegan inmediatamente al destinatario al apretar “send”. A pesar de esto, o gracias a esto, la correspondencia vuelve a estar presente en nuestra vida cotidiana. Hoy nos asomamos al correo electrónico muchas veces con la misma ansiedad con que en otras épocas corríamos a mirar el buzón.

Con otro estilo, con otro ritmo, pero aquí están las cartas, los mensajes… Ya no es el intercambio entre Sor Juana y una mentida Sor Filotea, o la carta de Lord Chandos justificando su silencio, o el epistolario entre Hanna Arendt y Martín Heidegger. Hoy la primacía la tiene lo instantáneo, lo inmediato, lo veloz.

Y sin embargo…

3.